How the Neanderthal Mind Shaped Religion

With a cognitive profile predisposed to pattern recognition and creativity, Neanderthals bridged science and religion, laying the foundation for later civilizations.

“The analogies between ceremonies documented at the farthest regions of the ecumene bear witness to a common tradition already developed during the Paleolithic.”

In shadowed caves beneath a sky unmarred by cities, humans observed the world for hundreds of thousands of years. Neanderthals persevered through the worst Mother Nature can offer—brutal and long ice ages, predatory megafauna, and continent-spanning natural disasters. Yet, their way of life emanates a simplicity that has long been dormant—one without the distractions and conveniences, the many miracles and horrors of civilization—that provided the opportunity to experience nature in its rawest, most tangible form. And unlike the nineteenth-century assumption of primitive dullness, the Neanderthal experience was aided by brainpower equaling, arguably surpassing, our own.

Religion is often assumed to have emerged alongside civilization, a late crown atop humanity’s restless mind. But what if its roots stretch deeper, to a people long misjudged? What if the fairy tales and traditions of untraceable origin are rooted in our Stone Age ancestors? Was there something identifiable in the Neanderthal experience—or cognitive profile—that would inspire the spark of religiosity in man?

If civilization is a slow remembering and myth a torch through prehistory’s darkness, then the first architects of knowledge may not be who we suspect. It’s time to reconsider the Neanderthal legacy—not as brute survivalists but as the first seekers of the divine.

The Neanderthal Brain

In the human brain, which averages 1,350 cubic centimeters, the prefrontal cortex generates abstract thought, including concepts of purpose and eternity. The parietal lobe integrates sensory input and spatial awareness, the occipital lobe refines visual perception, and the cerebellum fine-tunes movement, rhythm, and coordination.

Neanderthal brains, ranging from approximately 1,200 to 1,750 cc, surpassed modern human brain size and diverged in structure. Endocasts reveal an elongated skull, with an enlarged occipital lobe likely enhancing visual processing. The parietal lobe shows structural differences that may have influenced spatial cognition. Their prefrontal cortex was well-developed, supporting problem-solving and planning. A relatively smaller cerebellum may have influenced motor coordination and social cognition, possibly leading to distinct patterns of learning and interaction.

This wiring suggests a capacity for creativity and reverence. Their heightened occipital lobe sharpened vision, allowing them to track prey or observe the night sky with uncanny clarity. But this clarity was more than just physical—it shaped how they perceived connections in the natural world, revealing patterns of life, death, and renewal. A bear lumbering into a cave to 'die' in winter, only to emerge in spring with cubs, was not just a passing sight; it became a testament to the cycle of existence, reinforcing ideas of transformation, survival, and the image of the cave as both tomb and womb.

Neanderthal craftsmanship reinforces this notion. Their Levallois flake tools, struck with planned precision, reveal a mind capable of visualizing future outcomes. Their use of birch tar, distilled at exact temperatures, required methodical steps—mirroring ritual’s deliberate pacing. Their culture leaves more clues: Cueva de Ardales’ red ochre markings, 65,000 years old, combine visual acuity with symbolic intent. Bruniquel Cave’s stalagmite circles, built 176,000 years ago, stand as monuments to meaning rather than mere survival. The Shanidar burial, where a body was laid to rest with flowers, suggests death was not merely endured but marked, understood, and associated with rebirth. Even the first musical instrument—a flute carved from a cave bear’s femur—is a Neanderthal artifact. This brain cradled the first impulses of religious thought.

The Neurodivergent Neanderthal

Among these early humans, neurodivergence likely thrived—autism, in particular, providing a unique lens through which they saw the world. Today, autistic minds excel at spotting patterns: tracking a star’s shift, counting a herd’s steps, mapping chaos into order. They hyper-focus and perceive sensory detail with heightened clarity. Modern studies connect Neanderthal DNA—variants like rs7794745 on chromosome 7—to traits associated with autism: intense focus, sensory depth, and reduced social ease. Their smaller cerebellum (10-15% less than modern humans) and elongated brain suggest differences in social cognition, possibly placing less emphasis on complex group dynamics while heightening sensitivity to recurring natural patterns.

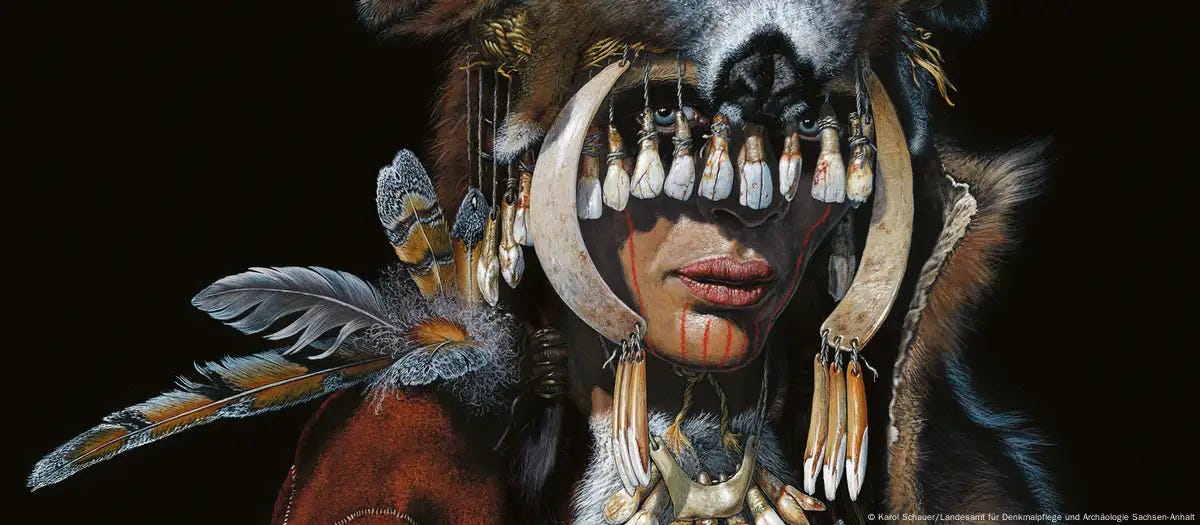

Hunter-gatherer life would have sharpened these abilities. Bands of twenty or thirty, tied to the land’s rhythms and reliant on its patterns, were undoubtedly aware of Orion’s rise signaling winter and salmon leaping from the river foretelling spring. An autistic Neanderthal might have fixated on these cycles to understand the patterns of nature, simultaneously increasing his chances of survival and revealing the sacred. The same minds that tracked migrations and celestial shifts would inevitably find meaning in repetition, laying the foundation for myth and ritual. Their burials—Shanidar’s flowers, La Chapelle’s careful interment—suggest an obsession with the significance of death and its proximity to creation. The bear skulls arranged in Chauvet, Drachenloch, and Unicorn Cave indicate reverence—pattern recognition evolving into sacred practice.

“In working with a piece of flint or primitive needle, in joining together animal hides or wooden planks, in preparing a fishhook or an arrowhead, in shaping a clay statuette, the imagination discovers unsuspected analogies among the different levels of the real; tools and objects are laden with countless symbolisms, the world of work - the micro-universe that absorbs the artisan’s attention for long hours - becomes a mysterious and sacred center, rich in meaning.”

This early evidence is the spark of religion. They were not simply surviving but seeking structure in nature’s chaos and meaning in its cycles. In their shadowed caves, the unseen took form, and the foundation of belief was laid.

The Cyclical Worldview

The cyclical worldview—the foundation of early religion—was not an invention of civilization but a legacy of the Neanderthal mind. Their heightened pattern recognition, deep connection to nature, and neurodivergent tendencies made them uniquely predisposed to viewing existence as a cycle rather than a linear progression. Life, death, and rebirth were not separate states but part of an eternal rhythm reflected universally.

Ancient civilizations, from Mesopotamia to Egypt, claimed inheritance from a distant, forgotten past often dismissed as mythological. Yet the same wisdom that shaped the pyramids, mapped the solar system, and inspired the longest-enduring myths in human history must have had an origin. Neanderthals seeded this perspective long before written language.

Their worldview persists. Our annual seasonal holidays that we instinctively maintain reflect an ancient reverence for the interconnectivity of nature’s cycles. The bear, central in so many traditions, also stands as an emblem of this inheritance. A bear that sleeps and rises again mirrors life’s ebb and flow—death as transition, not an end. Norse berserkers donned their skins, entering trance-like states. Sami rites honored them as kin. The mythic bear lingers across time: Beowulf (bee wolf = bear), Artemis, Arthur, Artio, Diana—the names change, but the reverence endures.

The Neanderthal legacy runs deeper than the stories we tell about them; it is embedded in the ways we perceive and interpret the world. Their way of thinking evolved from an intimate relationship with the landscape, animal life, and seasonal rhythms. That mindset favored symbolic association and layered meaning, leaving a lasting imprint on how humans respond to mystery. From those habits of perception emerged the earliest forms of ritual knowledge—ways of understanding reality that would later develop into religion, philosophy, and scientific inquiry. What we inherit from them is an entire mode of knowing we have yet to fully decipher.

Relevant Studies & Sources

Enrichment of a subset of Neanderthal polymorphisms in autistic probands and siblings – Molecular Psychiatry (2024). Link

Differences in the Neanderthal BRCA2 gene might be related to their distinctive cognitive profile – Frontiers in Neuroscience (2018). Link

(Quotes) Mircea Eliade – A History of Religious Ideas, Vol. 1 (1978).

I AM ALWAYS TELLING PEOPLE THAT HUMANS WERE WAY MORE TAPPED IN DURING ANCIENT TIMES 😩

First, I want to thank you for the wonderful and insightful content shared on your posts. Bravo! When you mentioned Bruniquel cave, I wanted to share something. I watched a very rich documentary on Arte channel (it is available in YouTube, I believe) that detailed the discovery of the cave, the technical difficulties of its exploration and the way it was studied and analyzed since its discovery. The most important subject was, of course, the stalagmites in a circle, suggested to be a gathering / ritualistic place. Some time after, i came across an Instagram post where a Brazilian singer and musician was happily discovering how some random stalagmites could be played like percussive instruments, giving out a pure and harmonic sound, that went specially well with the happily naive way she was playing it. Immediately my mind zoomed back to Bruniquel... and I kept imagining that the circle in the center of the cave as a gigantic percussive organ inside a stone cathedral. Call it reverie, if you want, but I suppose that it could well be an hypothesis as well...