Immortality Rites in the Ancient World

The dying sun has always been marked by rituals, from the Paleolithic to Halloween. Can we trace their lineage?

“I am Osiris, I reappear through you. The gods are living in me, for I live and grow in the corn that sustains the Honored Ones. I cover the earth; whether I live or die, I am barley. I am not destroyed.”

Scholars have long explained the great mysteries of antiquity through the lens of agriculture. The Eleusinian rites in Greece, the Osiris cult in Egypt, and Samhain in the Celtic world are said to have drawn their meaning from the seasonal cycle of sowing and reaping, the burial of seed and the cutting of grain. There is truth in this interpretation, but it begins the story too late. In the later years of Greece and Egypt, and still more in Rome which inherited from them, the source of the mysteries had grown distant, obscured by generations of prosperity. Their rituals were elaborate, their symbolism refined, but their original meaning had become half-forgotten. To understand their origin, we must look further back, into the Paleolithic, when men first entered the cave and enacted the descent into darkness as the price of renewal.

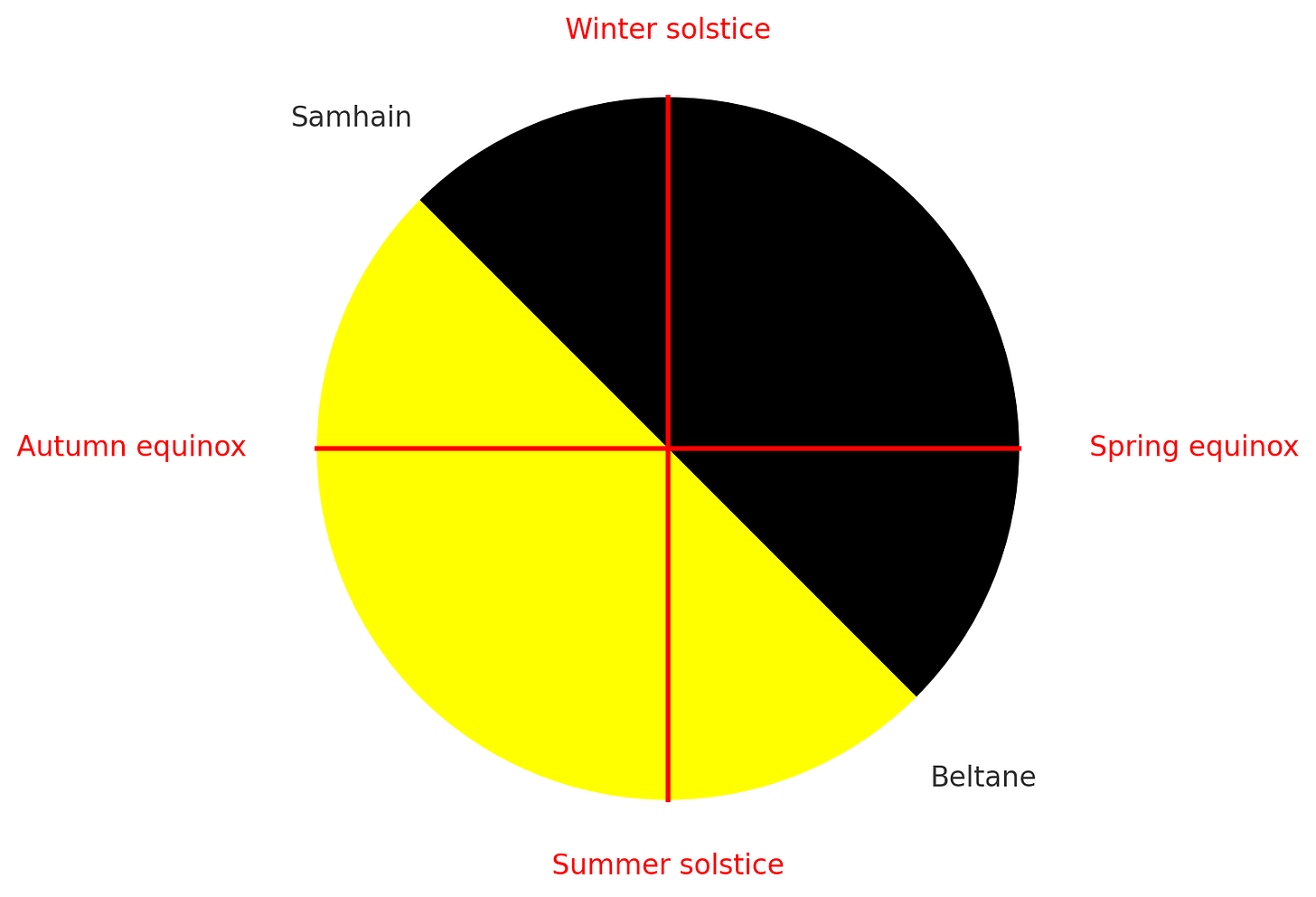

The equinoxes and solstices were the earliest annual markers and remain enduring thresholds. Twice each year the sun balances day and night; twice each year it stands at its extremes. Ancient peoples across the world watched for these days. Stone circles and tombs at Newgrange and Stonehenge show how carefully they were tracked, their axes aligned with the rising or setting sun. These were the hinges of the world, the fixed points by which the cosmos could be observed. The same pattern seen in the heavens was mirrored on earth, most clearly after the autumn equinox, when the dark begins to overtake the light.

Burrowing animals disappear into the earth to emerge in spring with offspring, as if born from the soil itself. Seeds fall to the ground, endure the cold, and are quickened under winter’s cover. The sun follows the same pattern, declining until it begins to rebound at the winter solstice. In the Paleolithic mind, these served as proofs that what recedes does not die without a trace, but will be reborn.

The Greeks clothed this logic in the myth of Persephone. Each autumn she was taken by Hades into the underworld, and her mother Demeter mourned until she returned. At Eleusis, this became the center of the greatest mystery cult of the classical world. Each year in September, just after the equinox, Athenians walked the Sacred Way to the sanctuary, reenacting Demeter’s search. There, in the darkened Telesterion, initiates underwent symbolic death and emerged into the promise of new life.

Ancient witnesses left us rare glimpses of its meaning. Cicero praised the Mysteries for teaching men “not only to live in joy, but to die with better hope.” Plutarch said they erased the fear of death. Plato spoke of the soul being opened to the realm of the gods. Aristotle remarked that the experience mattered more than knowledge. Yet to speak of the rites in detail was impious. They were to remain, as their name suggests, Mysteries—reflecting the hidden nature of what occurs underground, in the womb, and in the cave. Thus, though framed in agricultural imagery, the rite was the cave ritual made formal: a descent into darkness to discover immortality.

Egypt had long before elevated this conviction into an entire theology. The myth of Osiris tells of death, dismemberment, and resurrection, first attested in the Pyramid Texts around 2400 BCE, although almost certainly derived from more archaic oral traditions. Every dead man was identified with him: In death, the Pharaoh became Osiris and rose again in the stars. Over time, this privilege extended beyond kings to initiates into the Mysteries, as reflected in the Book of the Dead. Herodotus, writing in the fifth century BCE, explained to his Greek readers that the Egyptians were ‘the first to have maintained the doctrine of the immortality of the soul’ (Histories 2.123). And yet, Egyptians themselves claimed to have inherited it from a more ancient source.

The same pattern appears in the Celtic world, where the year was divided at the cross-quarter days, the midpoints between solstice and equinox. Samhain, on November 1, fell halfway between the autumn equinox and the winter solstice, marking the true beginning of winter or the dark half of the year.

It has also been called the start of the Celtic year, the logic for which appears elsewhere: cycles begin in darkness. In Finnish tradition, the harvest festival of Kekri, considered the beginning of the new year, occurred approximately on modern-day Halloween and honored ancestors who were thought to visit at that liminal time. As the Japanese folklorist Kunio Yanagita observed, ‘We thought in terms of evening to morning, not morning to evening, in measuring a day…the boundary being set by the sinking sun.’ The new year, like the day, was planted at nightfall.

Early Irish sources describe Samhain as a liminal feast when the boundaries between worlds weakened. It was the season when the dead returned. Children begged at doors for food, embodying the dead who seek rebirth, like seeds seeking nourishment in the soil. The modern pumpkin, carved and lit from within, is a symbol in perfect continuity with this concept: a husk or a skull illuminated from within, death animated by the spark of life. Similarly, the Räbeliechtli processions in Switzerland, as well as other traditions across Europe, feature gourds and roots lit in kinship with Samhain customs and the later jack-o’-lantern.

Across the ocean, Día de los Muertos in Mexico expresses the same conviction. The Codex Borbonicus, one of the most important surviving Aztec manuscripts, records the festival months of Miccailhuitontli and Hueymiccailhuitl—feasts dedicated to the ancestors. Graves are still adorned, food and flowers prepared for the returning spirits. The season of descent is that of communion with the honorable dead and a revitalization of their memory.

The doctrines of rebirth and immortality underpinned these cultures, but their roots reached further back. What was dramatized in the Eleusinian hall or embalmed in the Egyptian tomb was already present in the caves of the Paleolithic: that descent into darkness was the condition of renewal.

If we return to the Paleolithic, we find the outlines of these later practices already in place. At sites such as Drachenloch in Switzerland and Regourdou in France, Neanderthals left behind traces of funerary monuments. In some caves, human and bear skulls appear to have been deliberately curated or displayed, leading scholars to suggest a form of early ‘head cult.’ Later, Romans accused the Celts of head-hunting, but this was less an act of barbarity than a practice of ancestral veneration—keeping the presence of the dead close at hand, preserving the skull as a vessel of spirit. The same impulse is recognizable in the carved pumpkin lit from within, or the skull imagery used by the Aztecs: the head as a symbol of continuity, a reminder that death did not sever the bond between the living and the departed.

The French researcher Marie Cachet has argued that Neanderthal children underwent initiatory rites within the cave at the seasonal threshold, later preserved in festivals such as Samhain and Halloween. Mirroring the bear’s descent into hibernation, Cachet suggests that a child initiate would enter a cave, representing the realm of the dead, in a symbolic effort to receive nourishment from the sleeping Ogress—the mythic she-bear figure who hoards enough sustenance to carry herself and her newborn cubs through the winter.

Archaeology offers glimpses of evidence that align with this hypothesis. The clay bear effigy at Montespan cave from the Upper Paleolithic may reflect a later, more symbolic version of the ritual (Halloween being its latest descendant). The footprints of a child alongside those of a dog at Chauvet, some 26,000 years ago, suggest the deliberate presence of youth in ritual cave settings. Elsewhere in Stone Age Europe, bear and human bones were closely associated in deliberate displays at burial sites.

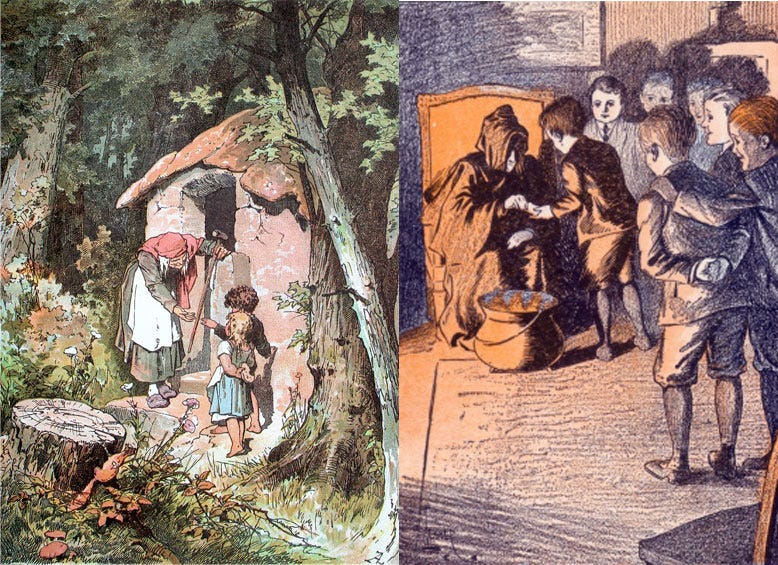

More significant is the mythological evidence of an unbroken archetypal lineage: the tale of the child or hero who descends into the underworld, faces harrowing trials, and returns renewed. This pattern surfaces in the great epics later catalogued by Joseph Campbell as the Hero’s Journey, but also in the more intimate form of fairy tales analyzed by Cachet in The Secret of the She-Bear. Such stories have no clear historical beginning; they must have started somewhere, and Cachet’s theory places their origins plausibly in the caves of the Paleolithic.

Concerning Halloween’s ancient roots, she points to “Hansel and Gretel” as a telling example. The children enter the otherworld through the forest, find a house made of sweets, and are enticed by a hard-of-sight, keen-of-smell Witch. Just as the she-bear will absorb unimplanted embryos during hibernation, the children risk being devoured by the deceptive Witch, unless they can escape the candy house—the womb—the cave. The fairy tale, like the ancient rite of initiation, preserves the same structure: descent, peril, and the possibility of renewal.

“Witches have red eyes, and cannot see far, but they have a keen scent like the beasts, and are aware when human beings draw near.” —Hansel and Gretel

Later civilizations inherited these intuitions and elaborated them into theology, liturgy, and seasonal festivals. Egypt embalmed them, Greece dramatized them, the Celts kept them in masks and fires, and we still celebrate this heavily symbolic annual festival centered around children inhabiting the spirit of the dead. But their origin lies deeper, where men first saw themselves reflected in the processes of the earth and drew the conclusion that has haunted humanity ever since: death is not the end, but the passage into continuity.

The autumn equinox is the balance before descent. Samhain is the entry into darkness. The solstice is the rebirth of light. At each stage, men shaped ritual life to the natural cycle, combining culture and science, art and philosophy. The bear entering its cave, the seed buried in the ground, the child dressed as the dead demanding food—all are figures of the same law: To die is to return. To descend is to prepare for renewal. Reincarnation and immortality are the first philosophy, a primal science drawn from the deepest observations of nature and enshrined in ritual from the Neanderthal caves to the cities of the ancient world, and into the customs we keep today.

Works Cited & Further Reading

Homeric Hymn to Demeter (7th c. BC).

Cicero, On the Laws, II.14.

Pyramid Texts (c. 2400 BC).

Tochmarc Emire (early Irish text, c. 9th c.).

Codex Borbonicus (16th c. Aztec codex).

Herodotus, Histories, 2.123. Translated by G. C. Macaulay (1890).

Anssi Alhonen, Notes on the Finnish Tradition (1992).

Kunio Yanagita, About our Ancestors (1945).

Emil Bächler, Das Drachenloch: Die vorgeschichtliche Bärenhöhle im Drachenloch ob Vättis (Kt. St. Gallen) (1923).

Marie Cachet, Le Secret de l’Ours (2015).

There seems to have been a gradual change, in many cultures, across the Stone Age, from communal burial spaces to individual graves. My own work has been in Ancient Egypt, but I did a broader anthropological study of burial practices at the beginning of my PhD. I came away with the notion that these stories carry in them that change in humanity's attitude, not just to death, but to the self.

If you take Osiris, his death is followed by corruption, decay and, in extreme versions of the story, dismemberment. It's a fate akin to ancient burial traditions that saw the deceased placed with many others. Such rites saw their identity fractured and dissolved, absorbed into a universal category of 'the Dead.' But Osiris emerges from this. His identity is not allowed to break apart and disappear.

He is reanimated, but the most important part of that reanimation is the denial of decay and the processes that threaten his personhood. His identity, distinct from the ubiquitous 'dead' is protected and preserved. I don't think it is a coincidence that his cult comes to prominence in Egypt at the same time as we start to see individuals keeping records of their lifetime's achievements in their tombs. At some point it became important to humanity to hold on to the uniqueness of members of their community.

The "dark and light halves of the year" are literally just the frost and frost free time periods for a gardener.