Le Regourdou: Evidence for the Neanderthal Bear Cult

First proposed in 1917, the "Bear Cult" theory is vindicated by this mid-century discovery.

There have been few major breakthroughs when it comes to our understanding of Neanderthals, but enough since their initial discovery in 1856 that we no longer question their intelligence. Their spiritual life, however, has been a subject of less clarity and more controversy. Anthropologists have been less involved in the Neanderthal question than archaeologists, so we’ve relied strictly on physical remains like fossils and tools instead of considering how our own spiritual traditions could be connected to those of our ancient ancestors, and what those could have been.

Le Regourdou is a Neanderthal burial site that is rarely cited by scholars. I can only assume that since, like Drachenloch, where the Neanderthal “Bear Cult” theory was first proposed by Emil Bächler in 1917, its primary significance lies in its cultural implications, the site tends to be overlooked in favor of less controversial sites.

Like Drachenloch, the cultural implications are strong. Bächler reported evidence of religious ritualism among Neanderthals who used bear bones as symbols in burial or initiation rites, thus viewing the bear as a sacred symbol connecting death and rebirth through the cave. Le Regourdou contained not only supporting evidence for Bächler’s once heavily criticized theory, but also the first discovery of its kind – a Neanderthal tomb.

In 1954, Le Regourdou was discovered by chance about a quarter of a mile away from Lascaux, the famous Upper Paleolithic cave art site, in France. Landowner Roger Constant had stumbled upon a sinkhole and took it upon himself to explore it, figuring it might be connected to Lascaux. When he came across part of a human skull, he brought it to the attention of local authorities who quickly deployed archaeologists to the scene.

After a brief spat between Constant, who felt inclined to continue excavations independently, and the university archaeologists, who insisted their expertise should take precedence, the two parties agreed (following the threat of arrest) to allow for shared responsibilities. The professionals would continue exploring where Constant found the skull. Constant could explore elsewhere.

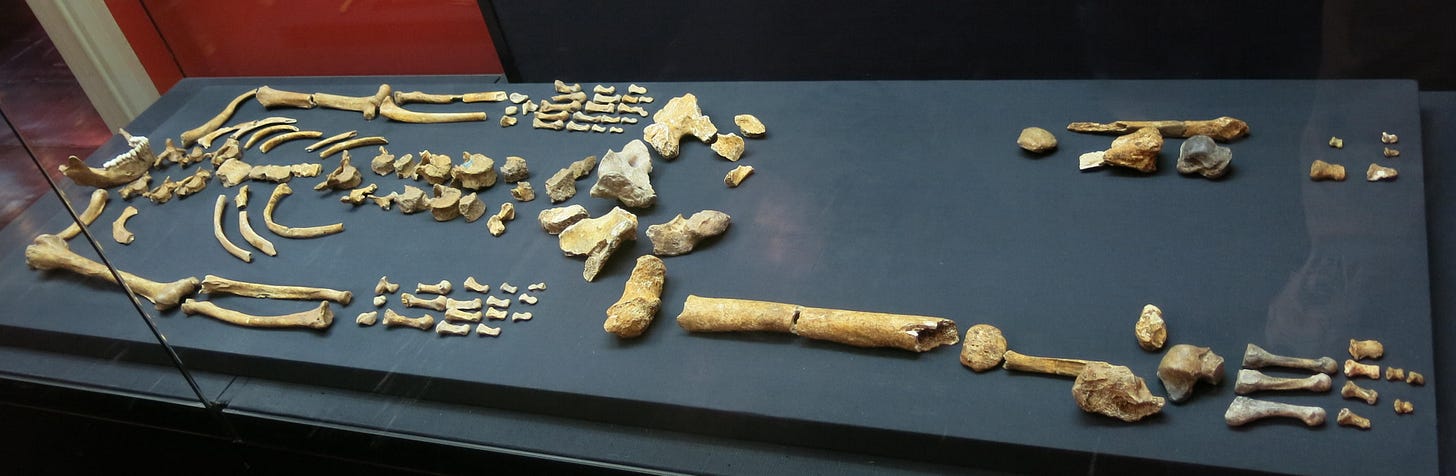

1957 saw the excavation of a near-complete 90,000 year old Neanderthal skeleton which remains the oldest most complete skeleton found to date (La Ferrassie 1 is more complete, but Le Regourdou is at least 30,000 years older). This alone makes it an exceptionally rare and important site, but we’ll focus on its ritualistic aspects.

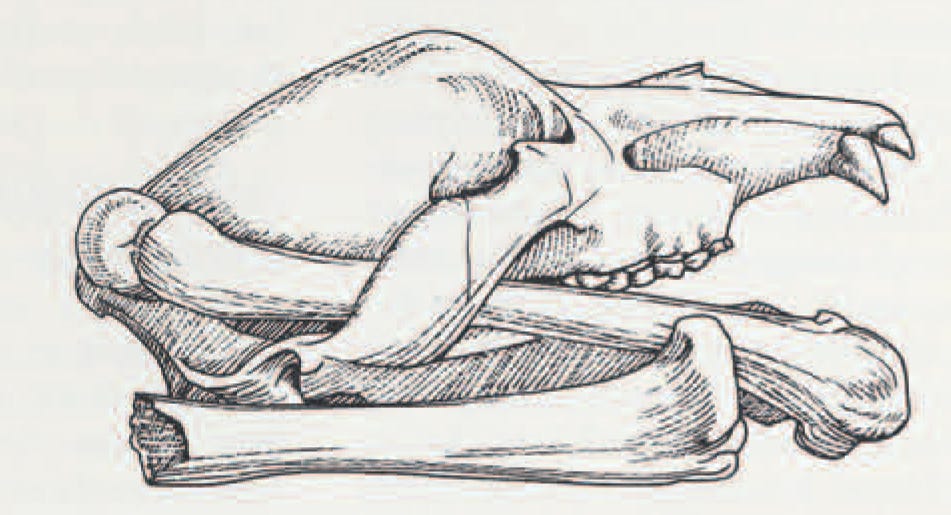

Missing parts of the skeleton include the jawbone, femurs and tibias. While Bonifay and excavating partner Georges Laplace didn’t speculate on the reason for their absence initially, it could have been assumed according to the Bear Cult theory that ritual was involved, since in the place of the missing Neanderthal femurs were those of brown bears — a curious arrangement that had been discovered at previous sites. But Bächler’s theory wouldn’t have been their first consideration.

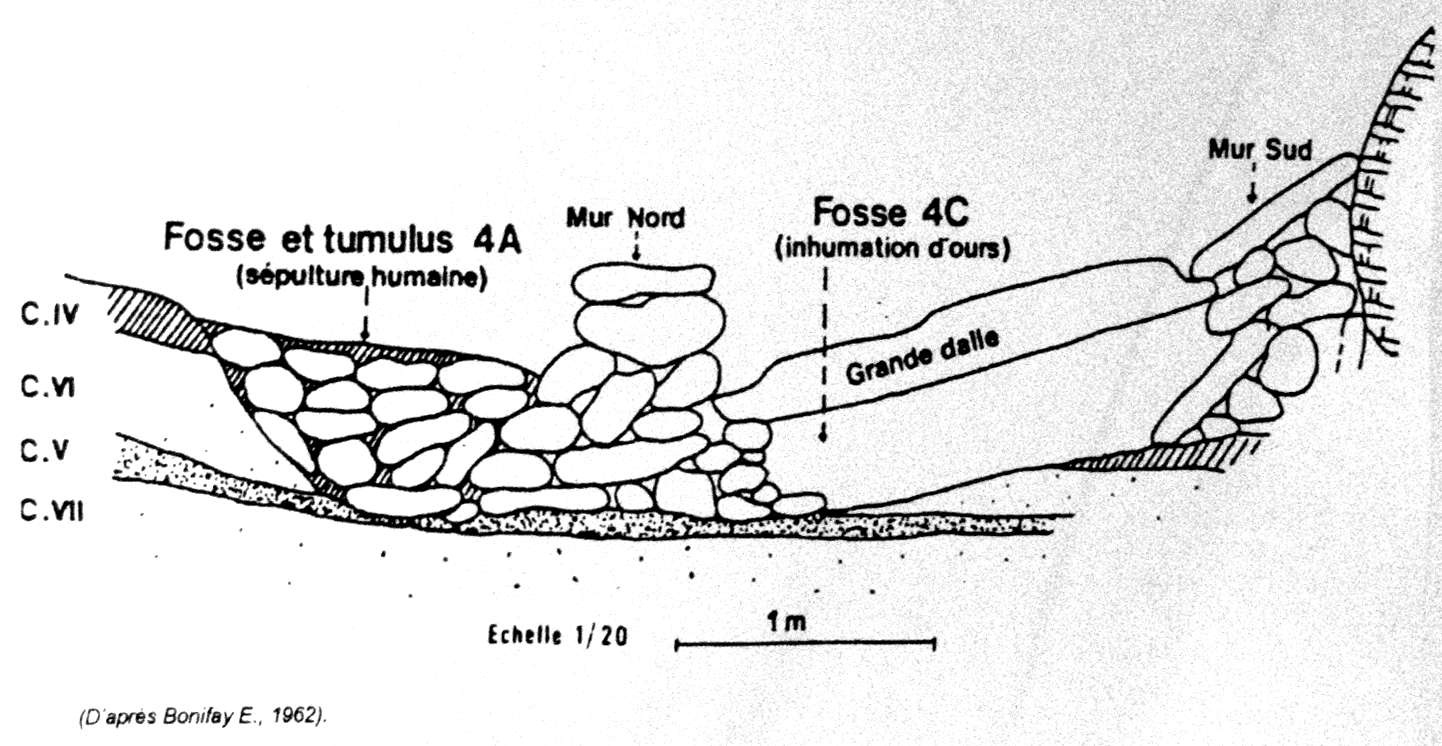

The skeleton was buried, head facing west, feet facing east, resting on top of a flat stone floor in fetal position. On the chest of the corpse rested part of a bear’s humerus and various flint tools. On either side of the body, two small parallel walls had been built, upon which rested a large limestone slab weighing nearly 800 kg (2,000 lbs). Described as “a real funerary monument” by Bonifay, the structure of Le Regourdou would be evoked by the dolmens of Europe thousands of years later. The construction of the tomb serves the purpose of a cave – symbolically they echo the same sentiment. Instead of a cave’s opening, the Regourdou tomb is accessed underground through an apparently naturally occurring portal that’s been named “Constant’s Chimney.”

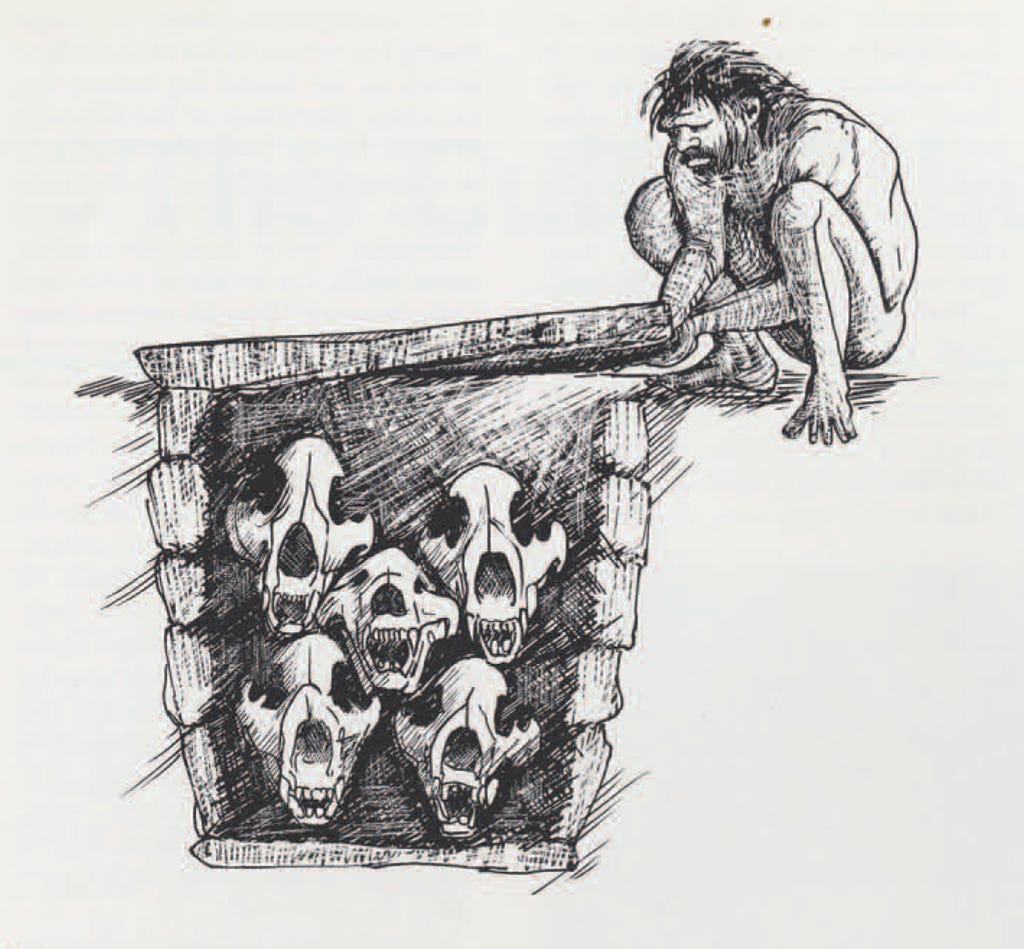

“Many stones [including tools], bear bones and a deer antler were then stacked together to form a small mound above the grave, then a fireplace covered the entire grave,” leading Bonifay to conclude the intentionality of the construction and burial. Similarly to Drachenloch, the entombment was impressively flanked by “about twenty stone boxes which contained the bones of [brown] bears.” Observations made with the assistance of Bernard Vandsermeersch further confirm anthropogenic origin of the structure based on “arrangement of equipment, stone paving, internal formwork protecting a bear skull…[and] stones brought from the outside.”

The most conspicuously arranged bear remains were that of a small female bear which were placed along the sides of the tomb with “the two shoulder blades crossed at the south end, [and] the skull rested between three stones forming a small protective formwork [to the north].” The others, studied by Marie-Françoise Bonifay, are noticeably separated between the thoracic skeleton, which were found outside the tomb area, and the skulls and femurs found inside.

The exact context of bears in the whole of Le Regourdou is debated. Throughout the site’s multiple layers, bear remains make up over two thirds of all faunal material, but questions surround the extent of man’s role in the entirety of their presence. Striations on bones and “differential spatial distribution” (namely the placement of skulls and femurs inside the structure) are the main exhibits for the case for human involvement. Bone markings could be the result of hunting, skinning, or marrow extraction as in the case of reindeer bones, ten percent of which are marked strongly by man-made fractures. It’s been suggested based on the wide diversity of herbivorous and carnivorous animal remains that perhaps the natural sinkhole was set up as some kind of hunting trap.

It’s also possible that bear mortality, since the vast majority of remains are of juvenile, occurred during hibernation. However, the prominence of juvenile bears will be later recalled during excavations in the Carpathian Mountains of Romania, where archaeologist Cristian Lascu suggested that young bears could have been hunted during an initiation rite for young Neanderthal hunters.

Bonifay concluded that most bear remains at Le Regourdou were placed by Neanderthals, but this has been reasonably contested by evidence pointing to bears having occupied the deposit independently. What’s not disputed is that Neanderthals interacted with and specifically arranged the faunal remains where the human burial is.

When all the evidence from is taken into account, the anthropogenic nature of treatment of remains is wholly apparent. Even the critical paper cited by Wikipedia as proof of “natural taphonomic phenomena” repeatedly confirms not only human involvement, but the likelihood of ritualism which at least partially confirms Bächler’s supposedly null Bear Cult theory. Bonifay, who was brought onto the site as an authority to the dismay of self-proclaimed “free-prehistorian” Roger Constant, aligned his opinion on Le Regourdou publicly with Bächler’s ideas in 2008, long after they all but faded into obscurity:

“Neanderthals made these deposits of bear bones to celebrate the death of one of their own…The bear was a powerful symbol closely associated with death. It may have evoked the idea of rebirth for Neanderthals by the fact that it hibernates in winter and reappears in spring, at the same time as the renewal of the entire natural environment, as if it ‘resurrected’ after its temporary disappearance.”

In the scientific community, as in Nadia Cavanhié’s 2011 paper “The Bear Who Saw the Man?: Archaeozoological and taphonomic study of the Middle Paleolithic site of Regourdou,” the term ‘symbolic’ is deemed too vague a label for evidence that doesn’t appear to have practical purpose.

While isolated to Mousterian culture, the term ‘symbolic’ definitely falls short of understanding Neanderthal culture. However if considered alongside the fact that Neanderthals are a progenitor species to many modern humans, the themes of their symbolic practices could be investigated as a worldview with the same foundational principles as the indigenous cultures of the northern hemisphere, aspects of which could remain in our customs today. Especially since they are repeated in multiple sites, ‘symbolic’ is a term that is now used with full utility.

While none of the sites immediately sparked theories about the exact significance of the skull, femur or bear, it had become obvious that they were ritualistic in nature. Le Regourdou echoes Bächler’s reports from Drachenloch thirty years prior, as well as elements from Veternica and Salzofen caves, and others. While not uniform in their similarities, the details of the grave sites are consistent enough to suggest a comprehensive culture dealing with the cyclical nature of life and death, symbolized by the cave (or tomb) and the bear. After all, some of the sites are dated tens of thousands of years apart from each other. Still, the prominence of the skull and femur, the particular arrangements of bear bones, and various other aspects are shockingly unwavering from 90,000 to 40,000 years ago.

Just found you! Right up my alley. Looking forward to more.

This calls to mind "Clan of the Cave Bear."