The Ancient Myth of the Sacred Twin

The silent companion dies so we may live.

“Nothing, in the end, was safe from the twins—not even the supports on which the world rests.”

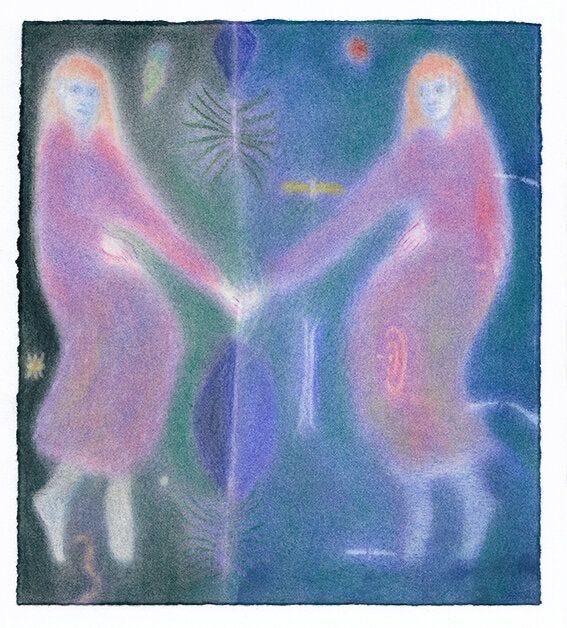

There is a silence beyond memory. It is not the silence of death, but of origin—the quiet before a name, before the severing.

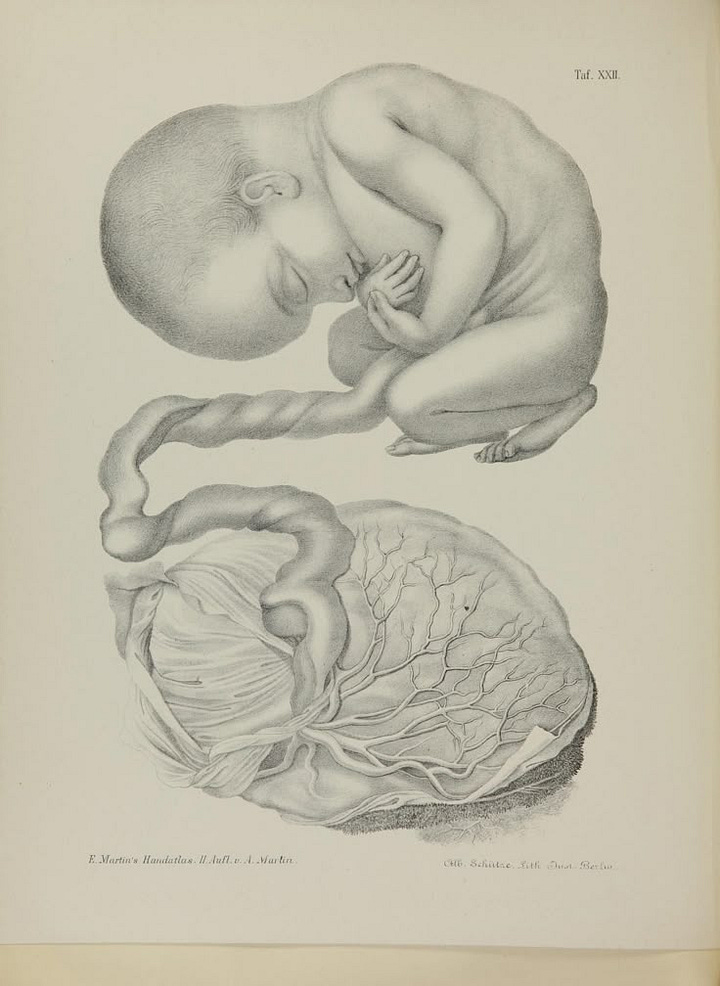

Somewhere, long before language, a child was born, and with him came another—a thing not quite a brother, but not less than one. It fed him throughout his uterine journey, a mentor of sorts, and when the birth thundered into motion, it died quietly beside him, its work complete.

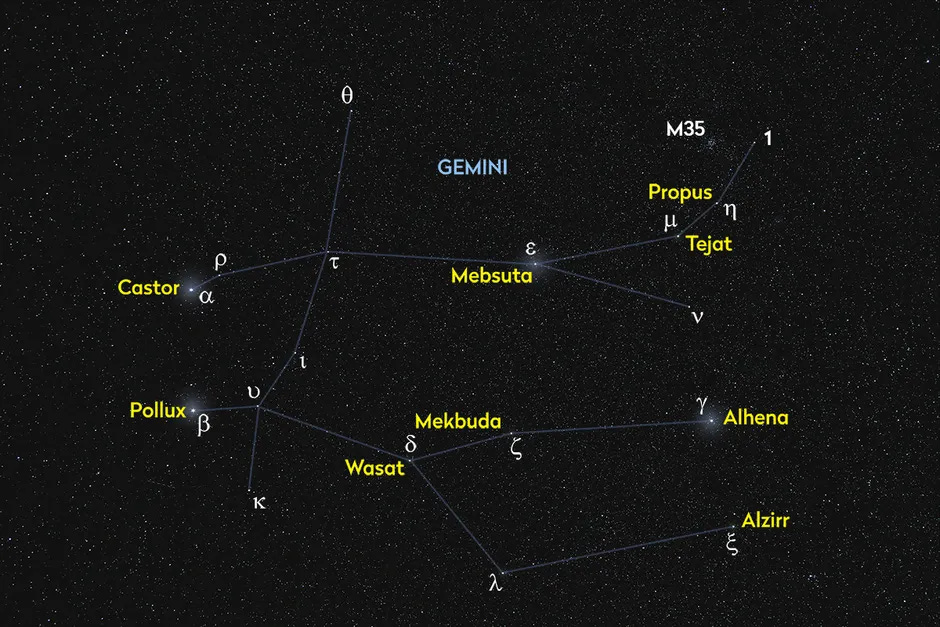

The impression of this enigma endured. It followed us out of the womb and into the world, shaping our stories, our symbols, and our perception of the world around us and above us. In time, we would see that pair of lights in the sky, the brightest stars of the constellation Gemini—so close, so constant—and remember.

It is this memory that gave rise to the myth of the twin.

The twin is one of humanity’s oldest and most enduring symbols, from the tales of Sumer and the Vedas, Greece and Rome, the Norse and the Maya, the Bible, and beyond. Wherever men have stood in awe of their origins, the mythical twin has loomed behind them as brother and rival, companion and sacrifice.

It is curious if taken at face value because real twins are rare. They are a biological aberration, yet they became the architects of mythic worlds: In the Popul Vhu, the sacred book of the Maya, Hunahpu and Xbalanque descended into the underworld to defeat death and clear the way for the age of humankind. The rivalry between Romulus and Remus ended in fratricide and the founding of Rome. Castor and Pollux (whose names mean “beaver” and “sweet” respectively, i.e., one who gnaws and one who is gnawed on), though not creators, became symbols of sacrifice and divine reunion—one mortal, one immortal—transfigured into stars that rise and fall together in the sky.

Again and again, myth begins with a separation: a double lost, a brother killed, a unity broken. Why?

The answer may lie in biology—more precisely, in birth. The ancients, deprived of modern anatomy, were rich in intuition. They saw what science now confirms: that each child enters the world with a double. The placenta is, in truth, the first companion of life. It is formed of the same substance at the same time. It feeds, it breathes, it sustains. It dies so the infant may live. In modern hospitals, it is discarded. But there was a time when people revered this “tree of life” as a guardian, ancestor, and totem.

Thus was born, in the earliest mind, the idea of the sacred twin: a being inseparable from the self, but doomed to disappear. In some traditions, this twin was buried beneath the home or a tree; in others, it was named and revered. Among the Maori, it was called whenua—a word meaning both land and placenta. The Navajo buried it near the home. The Balinese regarded it as the elder sibling. In Ancient Egypt, the placenta was known as the Pharaoh’s twin.

The Struggle for Birth

Francis Mott, in his meditations on birth, claimed that all our emotional life is “the desperate search for the lost uterine twin.” The soul, he said, longs not only for wholeness but for reunion. Isis, in her sorrowful search for Osiris, carries the memory of the placenta—the twin dismembered, the breathless god. In the Old Testament, Samson, whose name means “sunlight,” marries a woman named Timnath—meaning “twin.” The light-child and his dark reflection, bound and lost. Similarly, the Norse Baldr (“shining one”) has a blind twin named Höðr.

Carl Jung said that the twin is the mirror of the soul: even in dreams, we remember the other one, the quiet one who did not speak. The Ho-Chunk have a saying: “Nothing, in the end, was safe from the twins—not even the supports on which the world rests.” Perhaps because, when we are severed from ourselves, everything trembles. The mother, the vessel of creation, is as threatened as we are.

Drawing from myth and embryology, Marie Cachet sees the placenta as the ancestor, the totem who must die so the child may be born. In her words, birth is not a passage but a struggle—a battle between the fetus and its twin. One must emerge; the other must yield—“like the fighting of bulls.” The young must push past the old, and in so doing, take its life.

The Constellation Gemini

Across cultures, the constellation Gemini has long been seen as a symbol of duality. The Babylonians knew its two bright stars as Lugal-irra and Meslamta-ea, divine twins who guarded the gates of the underworld. Their names—“The mighty lord who rises” and “He who comes forth from Meslam” (Meslam being a cultic name of the underworld temple of Nergal)—mirror the duality of the fetus and placenta. In pre-Islamic Arab tradition, the stars were known as Al-Taʾamān, “The Twins,” imagined as two children bound together in celestial companionship. In the Greco-Roman world, they became Castor and Pollux—one mortal, one divine—brothers who connect life to the underworld.

Astronomically, their difference is as striking as their visual closeness: Pollux is a bright orange giant, singular and enduring. Castor is a hidden sextuple system—a fractured multiplicity mistaken for unity. One star is whole and brilliant; the other is complex, unseen, and multiple. Pollux may represent the living child; Castor, the lost twin, the buried companion whose complexity belies its silence.

Gemini’s stars thus support not only the literal image of twins but a universal archetype of duality, separation, and mirrored existence—whether in womb, myth, or cosmos.

Paleolithic Inheritance

Like the Great Bear (Ursa Major), whose identity as a bear appears across Indigenous American, Siberian, and Greek traditions, Gemini’s twin stars were recognized as such across disparate civilizations—not by coincidence, but by inheritance. These patterns point to a shared symbolic ancestry, when the first sky-watchers—perhaps Neanderthals or their hybrid descendants—projected their inner experience onto the stars. The myth of the sacred twin was not only born in the womb, but carried into the heavens by those who had already intuited the first great mystery: that to be born is to be divided.

Here, then, is the great secret buried in myth: that our first act is not to breathe, but to separate. Not to live, but to part from the other half of ourselves. And in this division, we create the longing that gives rise to gods—to twins.

A brilliantly put together and very thought provoking observation! I felt a shift in my consciousness reading what you realised and made real for me, too!!

I know that the name Remus, like a mirror, reflects the name Sumer and Lati, Ital... and Roma/Amor city of Love....like many other 'bostrophaedoned' names pour forth their secrets to us by inverting them. This further reflection that yiu have shared adds additional depth to the realisation of what "twins" are all about.

A sacred 'birth-right', the acknowledging of the hidden one who fed and nurtured the fetus inside the mother, has been ignored by the modern West. Placentas are thrown away and not ever thought about again.

Living in Africa for over 60 years, I had heard of the tribes burying placentas under a newly planted tree that eventually the 'other one' would join in death to be buried alongside... both would then nourish the tree as it grew to full size! I had read that Native American Indigenous women of certain tribes eat the placenta for strength after giving birth. You have shown me so much more! Thank you! Big appreciation.

Love this! Great connections symbolically. It reminded me of the Greek myth about soulmates once being a whole then split by Zeus as punishment to forever be searching for their missing half