The Bear’s Son Tale: A Neanderthal Legacy

The world's most widespread folktale may echo a shared ancestral memory.

“I believe we have good grounds for considering that bear worship traces an unbroken line of descent from the altars of bear skulls, which Neanderthal built a hundred thousand years earlier.” —Stan Gooch

A Pan-Northern Hemisphere Myth

The Bear’s Son tale is one of the world’s most widely distributed folk narratives. The story follows a hero, often the offspring of a human mother and a bear father, whose supernatural strength and resilience set him apart. Raised in isolation or among animals, he embarks on a heroic journey, usually descending into an underworld or battling supernatural foes, often accompanied by companions with extraordinary abilities.

In 1910, Friedrich Panzer collected over 200 variants from across Eurasia. In a study conducted in 1959, researchers identified 57 Hungarian versions. In 1992, a study revealed that 120 variants existed in Scandinavia alone. Dr. Roslyn Frank notes that 47 versions of the Bear’s Son tale have been recorded in the Western Hemisphere—33 from Spanish America, nine from North American indigenous groups, and likely many more yet to be identified, highlighting the tale’s deep roots across human traditions.

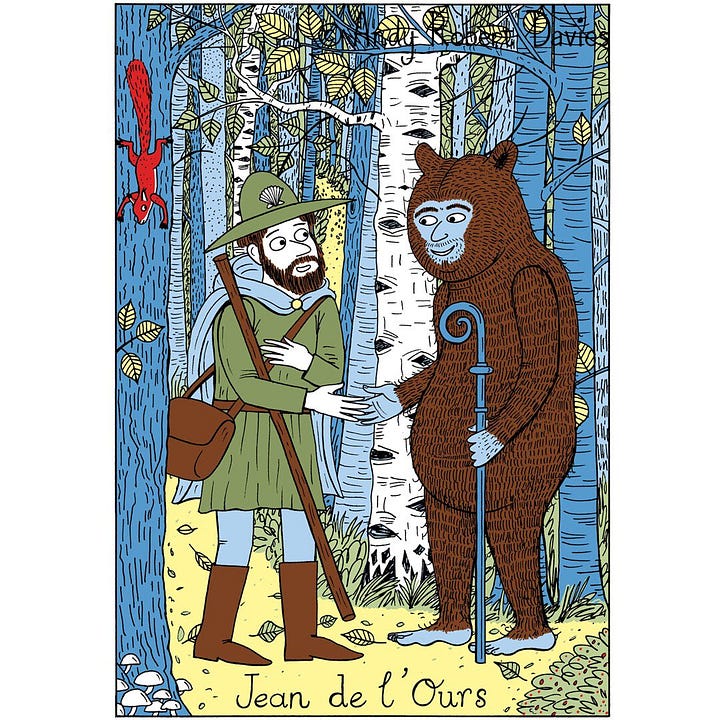

Famous variants include Beowulf, the Anglo-Saxon legend, in which the hero possesses extraordinary strength and battles a monstrous foe in an underworld-like setting, paralleling the trials of the Bear’s Son. Jean de l’Ours (John of the Bear) in France tells of a boy born to a woman and a bear, whose immense strength and adventures against supernatural foes mirror the core themes. Different versions vary in detail, but the recurring themes of a child with a bear connection, a bear-human marriage, and a heroic journey into the underworld reveal them to be branches of the same mythological tree.

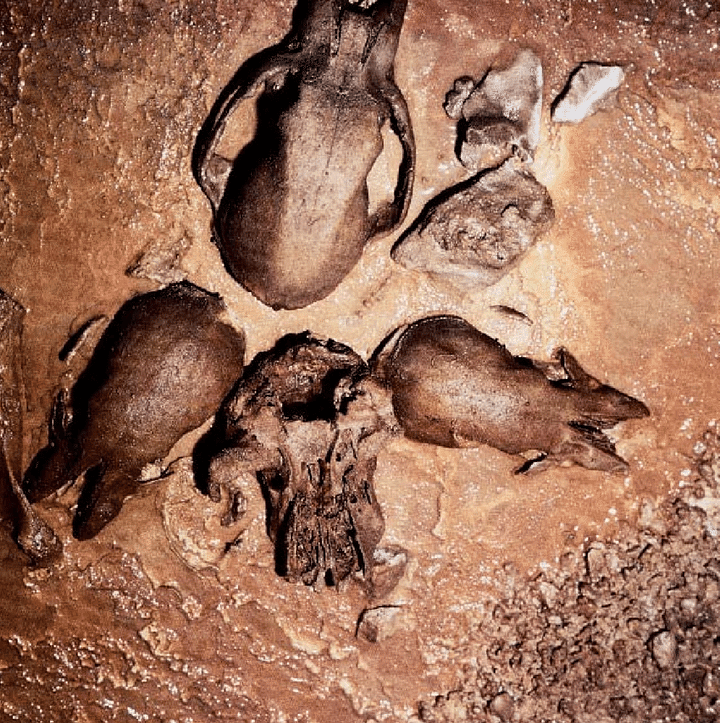

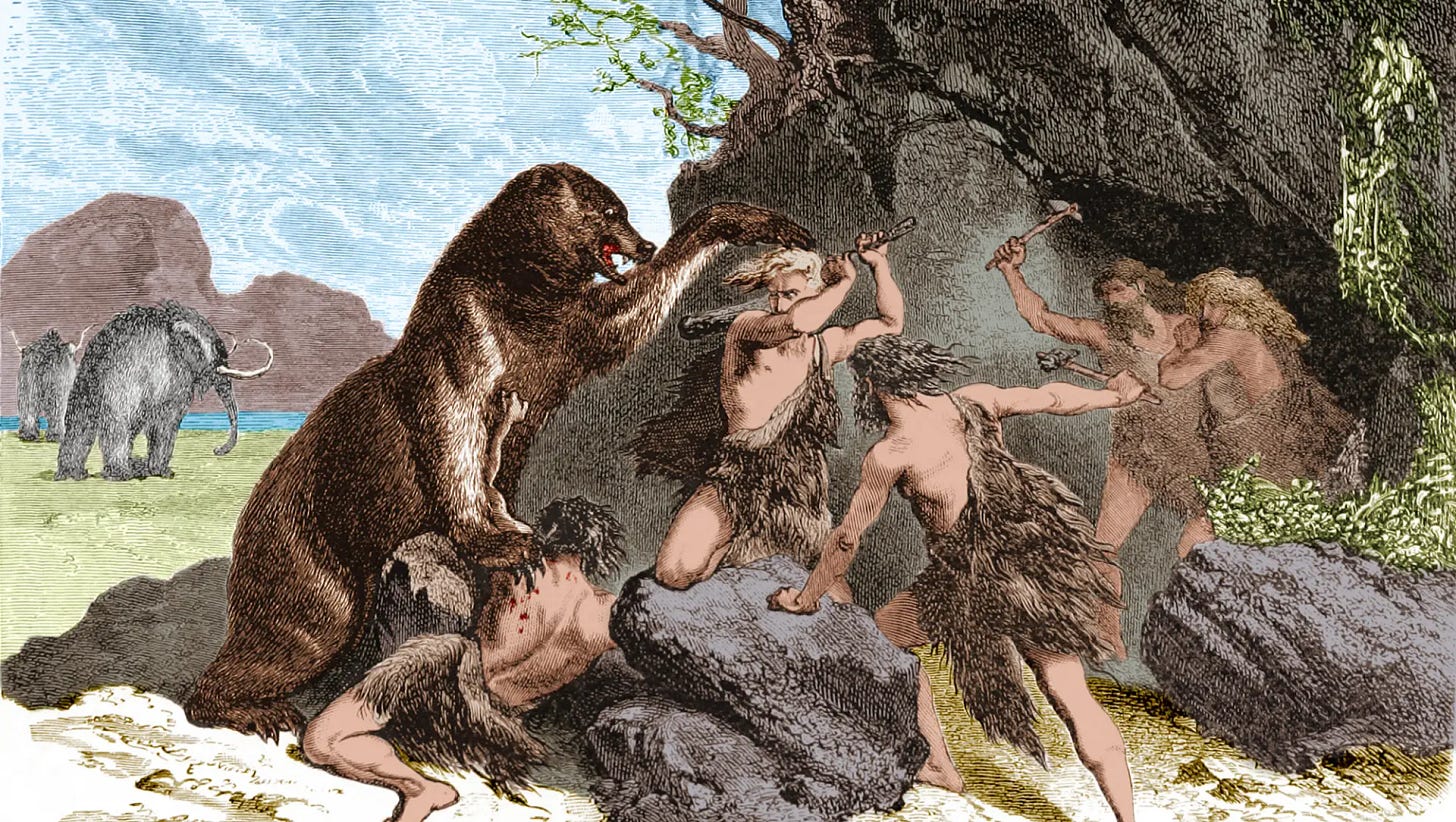

The tale’s circumpolar presence aligns with the ancient veneration of bears across the Northern Hemisphere. From the burial sites of Neanderthals like Drachenloch and Le Regourdou to the annual Bear Dance still performed in Romania, there is strong evidence that early humans and their predecessors viewed bears as spiritually significant as part of an unbroken lineage going back to the Stone Age. After their annual pantomime of death, the bear emerges in spring, encapsulating the ancient cyclical worldview of rebirth that underpins later traditions. The cave became a sacred analog for the womb, a place of transformation and rebirth, and the bear a symbol of the ancestor and the dangerous and venerable mysteries of the realm of death.

The migration of early humans across the Bering Strait provided a direct link between Eurasia and the Americas, making it plausible that not only genes but also deeply rooted spiritual beliefs, including bear veneration, were carried across ancient migration routes. The 2010 breakthrough in paleogenomics confirmed that Neanderthal DNA is present in modern human populations, creating a vacuum for renewed discussions about the potential for cultural and mythological inheritance. If Neanderthals engaged in ritualistic behavior related to bears, it is plausible that this reverence carried forward into our later traditions, evolving independently yet maintaining key structural elements.

Frank’s Colonial Transmission Hypothesis

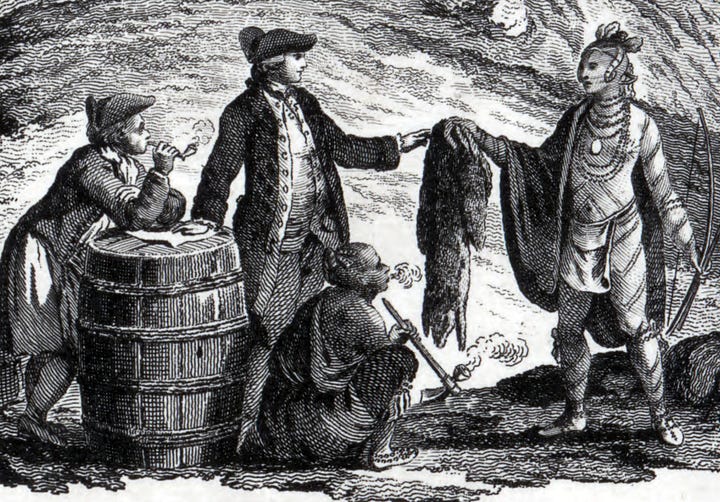

The questions of origin and transmission to determine how Native Americans could have folktales that mirror the famous Bear’s Son tale was addressed by Dr. Roslyn Frank in her 2023 article, The European Bear's Son Tale: Its Reception and Influence on Indigenous Oral Traditions in North America. Tracing the historical record, Frank follows seventeenth and eighteenth-century fur traders through French territory in the Americas and concludes that mercantile relationships between Native tribes and French traders fostered a deeper exchange. Natives resonated with the Bear’s Son tale, shared via a translator in meetings meant to warm trade relations, enough to absorb it into their own ancient canon.

While this is a compelling historical framework, it rests on the assumption that indigenous cultures were largely passive recipients of European stories rather than the bearers of their own deeply rooted mythological traditions. Frank’s analysis reflects a long-standing academic tendency to privilege direct historical documentation over broader anthropological and comparative methodologies. While colonial transmission undoubtedly played a role in certain cultural exchanges, the widespread presence of the Bear’s Son tale across regions outside of French or even European influence suggests an independent origin—one that reaches far beyond the written record.

The Improbability of French Traders Reshaping Native Mythology

The idea that French fur traders, operating primarily in limited areas of North America, could have influenced the mythological landscape of the entire continent is improbable. Frank notes that variants of the Bear’s Son tale exist in multiple Native American languages, implying that it was circulated between tribes after the traders imparted the tale onto an eagerly impressionable audience. While French traders and indigenous peoples did form partnerships, these were largely economic and pragmatic rather than a deep cultural exchange. Unlike Christian missionaries, who explicitly sought to impose their religious doctrines, fur traders had no such incentive. Their priority was trade, not mythological conversion.

Additionally, although the French territory in North America was large, encompassing most of the Mississippi River Valley and the Great Lakes region, French trade routes were geographically constrained. Technically, they could have interacted with peoples such as the Algonquin, Cree, Ho-Chunk, and even the Inuit to the far north, who tell variants of the Bear’s Son tale. However, similar stories appear where French influence was minimal or non-existent, such as among the Tlingit and Haida tribes of the southeastern coast of Alaska and British Columbia, far from the main French fur trade hubs.

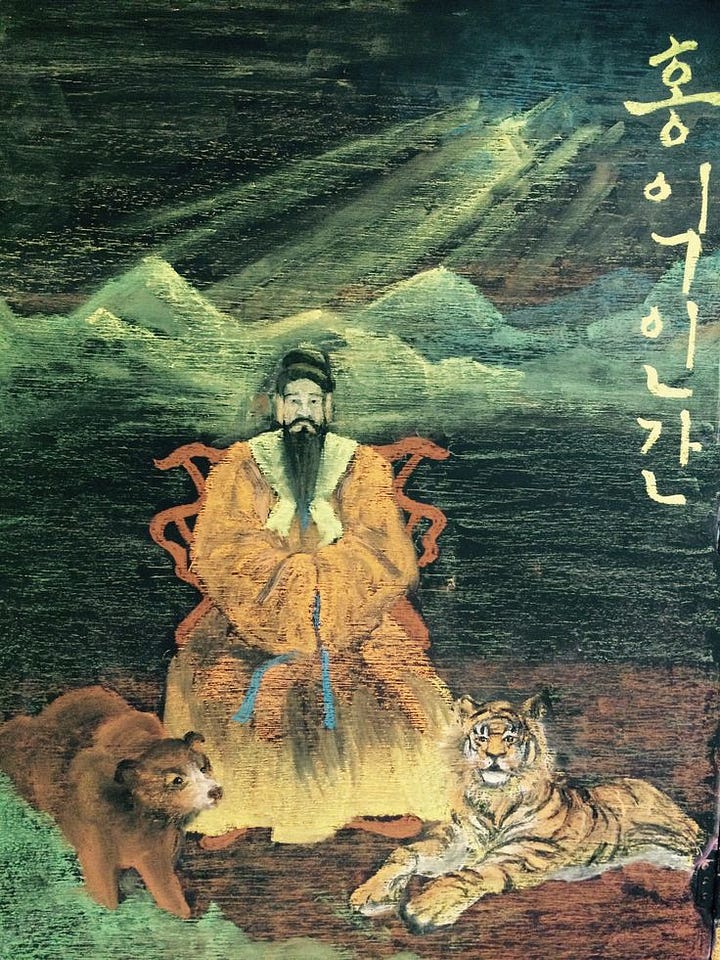

Motifs of the Bear’s Son tale exist in the East as well. In a Korean creation myth, a bear transforms into a woman, marries a heavenly prince, and gives birth to Dangun, the founder of Korea. Siberian tribes such as the Evenki and Khanty share bear myths where a child is raised by or born of a bear. The Ainu people of Japan famously revere the bear as a divine ancestor and have myths of bear-human hybrids and strong heroes with bear-like traits.

Frank herself acknowledges the cultural barriers to the sharing of sacred traditions. She notes that the Basques, with whom she has conducted extensive research, were "always careful not to share” the idea that their people descended from bears with non-Basque speakers. This secrecy is a common trait of indigenous oral traditions. Although the Catholic French traders might have had fewer qualms with sharing their indigenous tales if they suspected it would help trade, the Natives themselves would have likely been more protective of their already threatened heritage. The assumption that indigenous people would readily absorb and integrate a foreign folktale into their mythological framework without resistance underestimates their cultural autonomy.

A Common Inheritance

Beyond the Bear’s Son tale, other cultural overlaps between pre-Christian Europe and Native America suggest a deeper shared inheritance. Both exhibit totemic animal relationships, gods and goddesses representing natural forces including trickster deities, vision quests as rites of passage, and the cyclical, animist worldview often called “paganism.” The Great Flood myth, also found in both traditions, suggests an Ice Age-era memory preserved in folklore or perhaps something more psychologically embedded from a common ancestor.

Even among Bear-related myths, the Bear’s Son tale is not an isolated instance of mythological parallelism but part of a broader cultural framework. Native American warriors channeled the strength and spirit of the bear in battle, much like Norse berserkers, who were believed to draw power from them. The Haida people believe in a divine Bear Mother who gave birth to children with a bear husband, a theme echoed in the European Jean de l’Ours and the Greek tale of Callisto, a woman turned into a bear and later immortalized as the constellation Ursa Major. Why Native Americans and Europeans both referred to this constellation as the “Great Bear” is another unanswered question.

This broader perspective suggests that the Bear’s Son tale is not a singularly European export but part of an inherited mythological tradition that spans millennia. It is unlikely that the core similarities between these narratives are the result of colonial diffusion when their geographic distribution predates European expansion. Instead, they point to an Ice Age-era inheritance of symbolic bear veneration that persisted across multiple cultures and populations, evolving along different but parallel trajectories.

The Paleolithic Connection: Neanderthal and Early Human Bear Worship

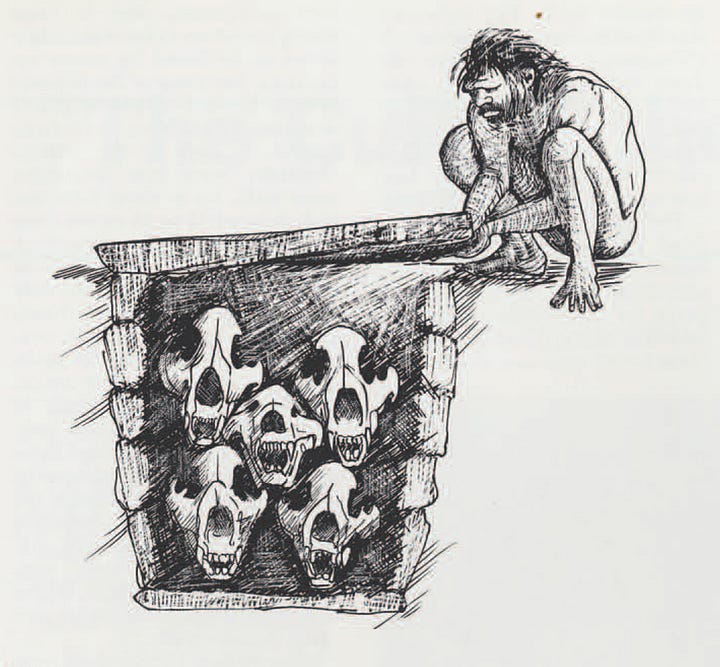

Looking further back in time, the evidence for bear-related spiritual traditions among prehistoric humans reinforces this argument. Archaeological sites associated with Neanderthals and early Europeans show striking evidence of bear veneration. The ritual placement of bear skulls and femurs suggest that Neanderthals saw the bear as more than just competition for vital resources, and aligns with later traditions in which bears are depicted as ancestors or divine beings.

Mythologically, marriage represents not a physical consummation but a symbolic pairing of forces. A bear-human marriage thereby imbues the human offspring with qualities associated with bears like extraordinary strength and the ability to descend into the otherworld and re-emerge transformed. Ancient man likely not only associated the bear with strength for obvious reasons but also the hyper-awareness and adrenaline the bear instilled in men in times of confrontation. As the clay bear figure in Montespan Cave suggests (among other Neanderthal sites), the bear was likely part of an initiation ritual that purposely struck the initiate with life-or-death hormonal surges—a reverent but also practical ritual in a hunter-gatherer society.

Rather than viewing the Bear’s Son tale as a recent European export, it should be understood as part of an ancient and widespread mythological inheritance. Frank’s work provides an important historical framework, but it falls into the common academic trap of prioritizing documented colonial interactions over broader anthropological and genetic evidence. The similarities between bear myths across Eurasia and the Americas point to a much older source—one that may date back to the shared cultural landscape of Ice Age peoples and, perhaps, even to our Neanderthal predecessors.

More than a tale of conquest or cultural exchange, the Bear’s Son narrative points to something far more primordial. It reflects a world in which humans and bears moved through the same landscapes, bound by reverence, fear, and kinship. The myth endures, not because it was imposed, but because it was always there, waiting to be remembered.

I’ve only just begun to scratch surface of the bear mythologies but what also comes to mind is I believe in Russia or in the Slavic nations, they refer to a mother/ woman who has conceived children as a bear, maybe in allusion to the bear like growls and grunts a woman makes in childbirth

I’ve also heard it argued that the goddess Artemis who’s animal is the bear and is sometimes called the she bear and young maidens or priestesses in training to her would perform initiations by “playing the bear” in veneration to Artemis. However I’ve heard some historians claim that Artemis is one of the older goddesses, and existed pre Greek and stems from one of the primordial mother goddesses

Then we also have the proto Celtic word “artos” meaning bear which we find in similar words like Artemis, and Arthur of the round table legends and “arktos” the Greek for bear, from which I think we get words like arctic like the arctic circle where we find many bears. Perhaps alluding to northern symbolism

This essay is so good, thank you. This: “an inherited mythological tradition that spans millennia” Yes!