The Fetal Journey is the Hero’s Journey

The fight for birth aligns with humanity’s most defining archetype and explains its origin.

Every hero’s tale begins in a place we’ve all known. Before myth or scripture, there was the struggle to be born—the first journey out of darkness, through peril, and into the world. We recognize its pattern in every epic because it never left us: the descent and return, the death and renewal. These stories endure because they echo the rhythms we first lived in the womb.

Everything occurs in cycles. Whatever one observes, from pop culture to the rise and fall of civilizations, from microbiology to the stars, or flora and fauna of the earth, everything “new” contains the seed of its predecessor, and everything dying and dead contributes to the beginning of the next cycle.

Applied to man, manifested through genes and memory, death and rebirth are the cornerstone of ancient spiritual belief—but it was not only revered symbolically. Humans strive to understand existence and to pass down knowledge so it compounds into a greater and greater understanding. In the ancient world, they developed traditions and stories—weaving knowledge into both to preserve it through the ages.

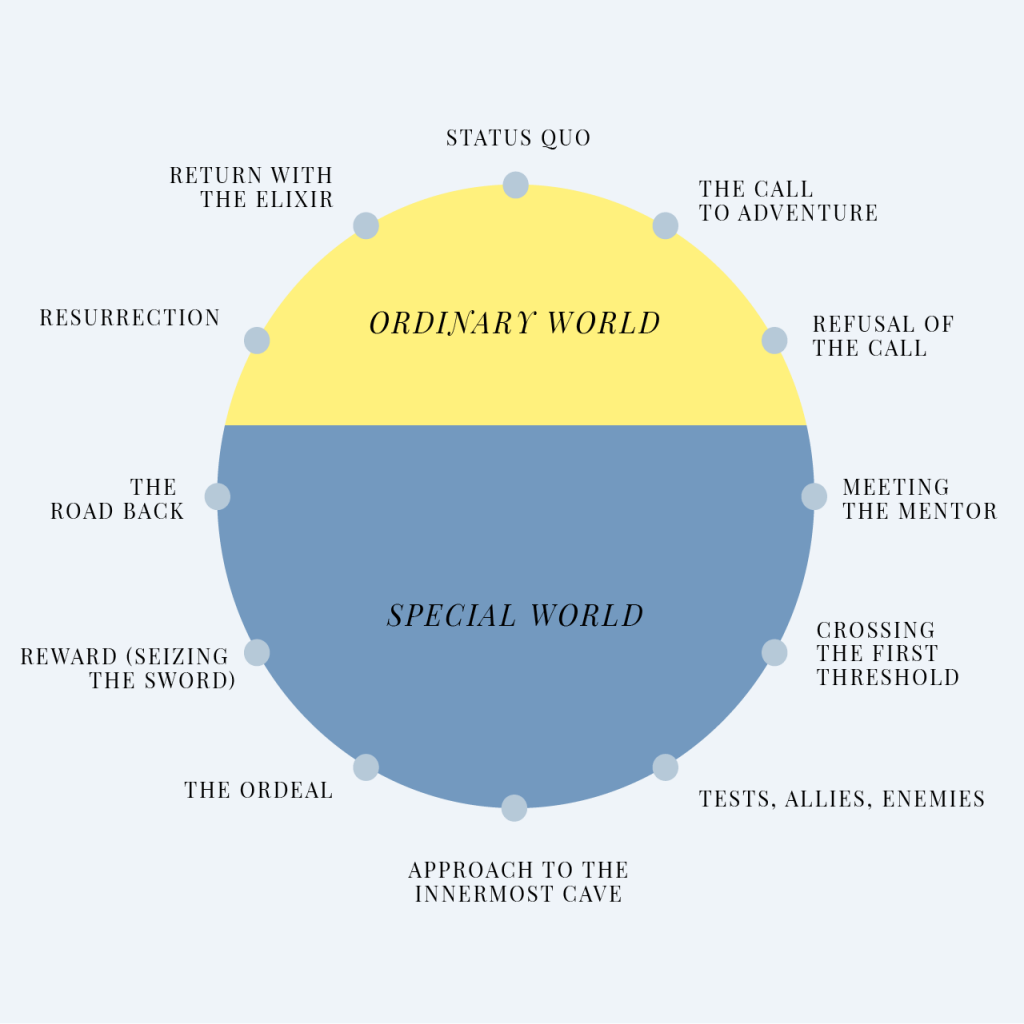

The Hero’s Journey, famously identified and mapped by Joseph Campbell in The Hero with a Thousand Faces, is the story arc followed by humanity’s most defining and universal characters from Odysseus, Gilgamesh, and Beowulf, to modern examples like Luke Skywalker, Frodo Baggins, Chihiro from Spirited Away, Simba from the Lion King, and many more.

Although the Epic of Gilgamesh has been credited as the first example of the Hero’s Journey, many older fairy tales whose origins are lost in the depths of prehistory suggest otherwise. It was not the advent of civilization and writing that spawned this universal archetype, but something older and more profound.

What was the blueprint for the Hero’s Journey?

Science existed in prehistory—but instead of formulas and charts, they used myth and ritual. Even in esteemed ancient civilizations, the barrier between science and religion as it stands today did not exist. When we identify the process of rebirth as a point of reverence for prehistoric people, it becomes possible to consider the application of modern science.

Therefore, we will look to the (still) mysterious realm of the womb, where the fight for birth, although veiled, is as treacherous and heroic as any tale of epic adventure. Drawing from developmental biology and fetology, we can map the Hero’s Journey directly onto human development in utero. Recognizing that this archetype is shared across cultures without a known first instance opens the door to a deeper origin of this archetype and a more sophisticated understanding of creation in the remote past.

Fetal Equivalents for the 12 Stages of the Hero’s Journey

1. The Ordinary World: Pre-implantation existence

The Hero begins in a place of comfort and familiarity. In the fetal version, this is the earliest stage: the fertilized egg (zygote) drifts through the fallopian tube, not yet attached to the uterine wall. It is a wanderer, full of potential but without form or direction—much like the archetypal farm boy or hidden princess, unaware of their destiny.

2. The Call to Adventure: Implantation into the uterine wall (~Day 6–10)

This is the moment the embryo accepts the “quest”—embedding itself in the uterine lining and committing to the path of development. Biologically, this is a critical threshold. Failure here means the end of the journey. Success means transformation begins.

3. Refusal of the Call/Threshold Guardians: Immunological challenges, chromosomal errors, miscarriage risks

Not all journeys are guaranteed. The body has mechanisms to reject embryos that seem genetically unviable. In this stage, maternal immune cells can act as “threshold guardians,” scrutinizing the newcomer. Many pregnancies end here, echoing myths where the hero turns back or is delayed before stepping into the unknown.

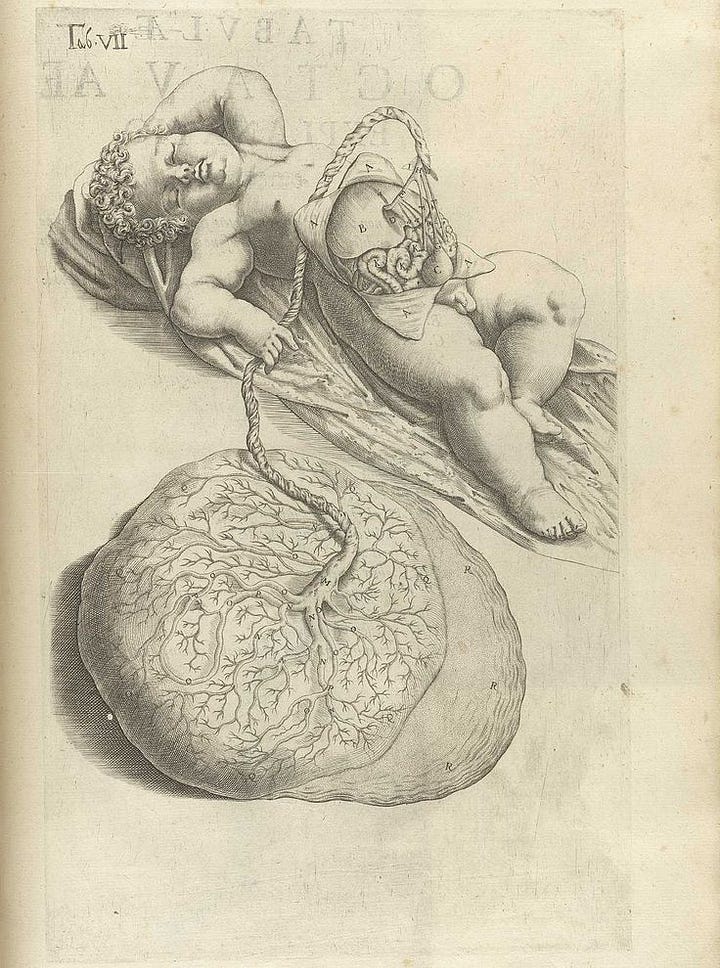

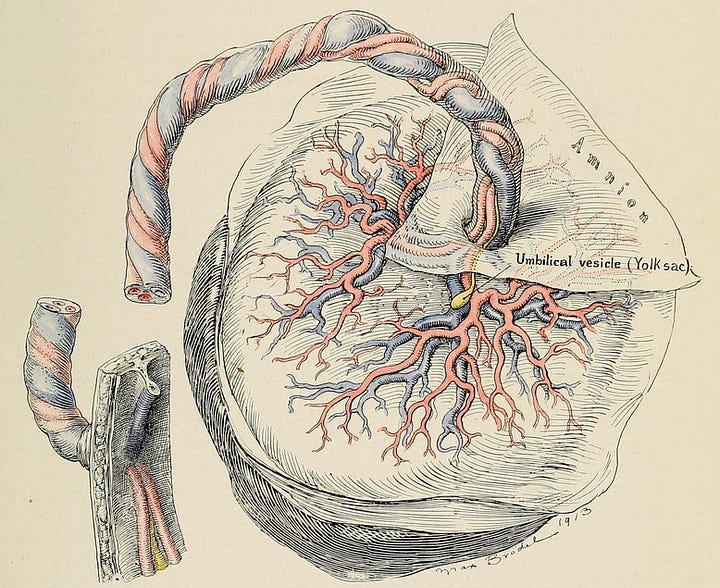

4. Meeting the Mentor: The placenta

Every hero finds guidance—a Gandalf, a Yoda, a fairy godmother. The placenta is this biological mentor: a mysterious, temporary organ formed from fetal and maternal tissues that resembles the tree of life. It filters, nourishes, and communicates. It also produces hormones that alter maternal physiology, making the external world safer for the developing hero.

5. Crossing the First Threshold: Gastrulation (~Week 3)

The embryo’s cells undergo dramatic internal rearrangement, forming the three germ layers (ectoderm, mesoderm, endoderm). This is when an amorphous blob becomes a structured being. It is, as biologist Lewis Wolpert put it in Principles of Development, “the most important moment of your life.” This is the first true transformation, a commitment to a form.

6. Tests, Allies, Enemies: Organogenesis, neural development, environmental interaction

The second trimester brings rapid development: the heart beats, the brain forms, and reflexes emerge. The fetus starts responding to touch and sound. Maternal stress hormones, infections, and toxins can act as “enemies,” while amniotic fluid, hormones, and nutrients are “allies.” This is the hero's trial—a crucible of growth.

At week 21, the fetal skin is fully developed and coated in tiny “Lanugo” hairs, which act as the “primary sense organ…which touches its limited watery environment equally in all directions.” In The Nature of the Self, Francis Mott suggests a connection between this ‘shining’ fetal sensation and the mythological archetype of the shining god.

7. Approach to the Inmost Cave: Late pregnancy (~Weeks 30–40)

The womb, once expansive and Edenic, becomes tight and dark. The fetus begins turning downward, preparing for birth. Neurological patterns consolidate; some memory and learning occur. In mythology, the “inmost cave” is where the greatest ordeal lies—often underground or symbolic of the unconscious. In biological terms, it is quite literally the womb itself.

In Neanderthal times, the cave was not just a shelter, but a sacred space, the terrestrial womb. To descend into the cave was to symbolically return to the origin—the dark, enclosed space where transformation occurs. Caves across Europe are where we find the first evidence for rituals, art, and burials surrounding their cyclical worldview.

8. The Ordeal/Death and Rebirth: Birth

No ordeal is greater than birth. The world turns upside-down. Fluid becomes air. The lungs scream to life. Compression, separation, and disorientation abound. The hero dies to the old self—fetal, fluid-borne—and is reborn as a breathing, independent being. In nearly every culture, this transition from darkness to light is echoed in ritual and myth.

“Rebirth” or reincarnation as a concept can be thought of strictly in scientific terms through DNA, which is made up of all one’s ancestors, whose earthly existence has been recycled into the “new” life. The modern study of epigenetics suggests that memory, behavior, and lifestyle all have their place in the genetic code.

This momentous “battle” ends with cutting the umbilical cord—the slaying of the final serpentine foe, often mirrored in this stage of the Hero’s Journey by the literal slaying of a threatening dragon or serpent (Hercules and the Hydra, Prince Philip and the dragon Maleficent, Harry Potter and the Basilisk).

9. The Reward: First breath, first cry, mother-child bond

The newborn seizes the “elixir”—life. The reward is connection: skin-to-skin contact, oxytocin bonding, warmth, and food. This is the treasure at the journey’s center, just as Luke receives the lightsaber or Neo sees the Matrix.

10. The Road Back: Adaptation to external life

The umbilical cord, which guided the fetus through the prenatal process, tying it to the placenta and the mother, was severed at birth. Gravity exerts force for the first time. Light, sound, digestion—all must be learned as sense shifts from the skin to the five orifices. This is the return from the dark realm. The newborn begins integrating into the world of others.

11. Resurrection: The “fourth trimester” (~First 3 months)

Neurologically, the newborn is still completing gestation outside the womb. This is a liminal time—known as the “perinatal” phase—neither fetal nor fully infant. Crying regulates the lungs; bonding patterns form that grounds the infant to the earth as it was once grounded to the placenta. This is a second transformation, where the Hero completes their rebirth into social, emotional, and sensory life.

12. Return with the Elixir: Conscious presence in the world

The infant brings the “elixir” back to the tribe: the future. A continuation of the lineage. New blood, new hope, new awareness. The Hero returns changed—and brings with them the potential to transform others.

An ancient memory experienced by all

If this structure is present across independent cultures, and if it reflects something as universal as birth, then its origin likely predates writing, agriculture, and even our current state as a species.

Since the mysteries of death and rebirth can be traced to the Neanderthal culture, we can assume that, if they aren’t explicitly responsible for this scientific archetype, its basis in the veneration of the unseen—the womb, the cave, the realm of transformation—was at least formed by our ancient ancestors. Paleolithic rites may well have reenacted the Hero’s Journey in ritual form.

The universality of the Hero’s Journey (and mythology in general) allows for various interpretations and applications, but perhaps at its core is a biological memory, one that was woven into human consciousness through narrative.

You have already made this passage once. Before you had words, you pressed through your first ordeal, descended into danger, and rose again into the world. The Hero’s Journey speaks to us not because it is familiar storytelling machinery, but because it repeats an older rhythm we once lived. Its memory settles deep in us—beneath thought, beneath awareness—and myth is simply the language we give to that ancient experience.

Myth is simply the language we give to that ancient experience.

I was swept away by this piece. In indigenous Maya culture we believe that the sacred calendar, the Tzolkin mirrors the path of human gestation and then mirrors again macro-cosmic cycles. Yes to everything you have written here beautifully. Words and articulation that goes beyond the mundane and into the primal. Instant subscribe