The Lost Book of Shinto

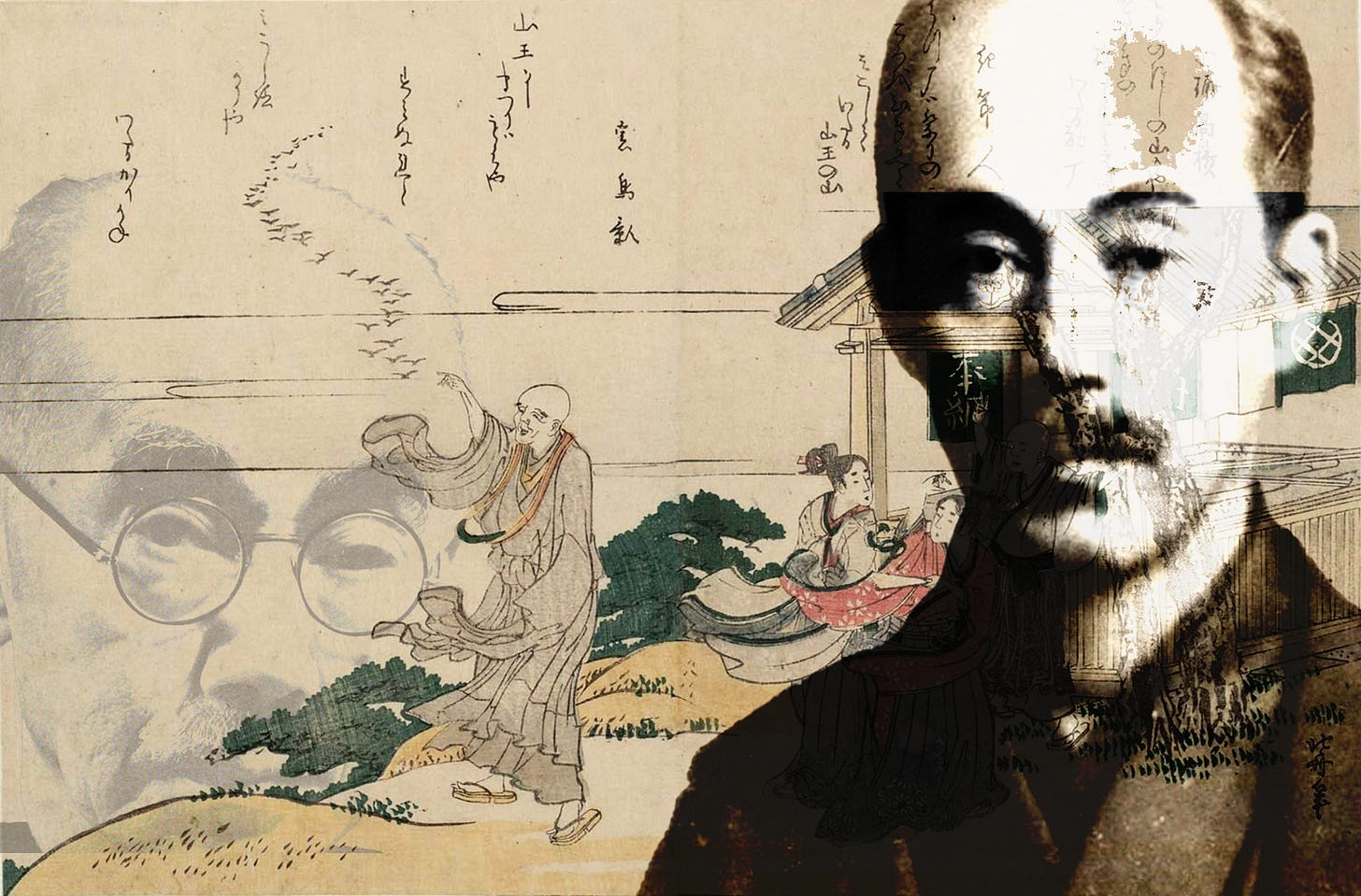

Kunio Yanagita’s Elusive Wartime Masterpiece on the Japanese Family System

“The afterlife of our people, the eternal existence of souls within our land and not in a distant place, has been firmly maintained from the beginning of the world until now.” —Kunio Yanagita

Author’s Note

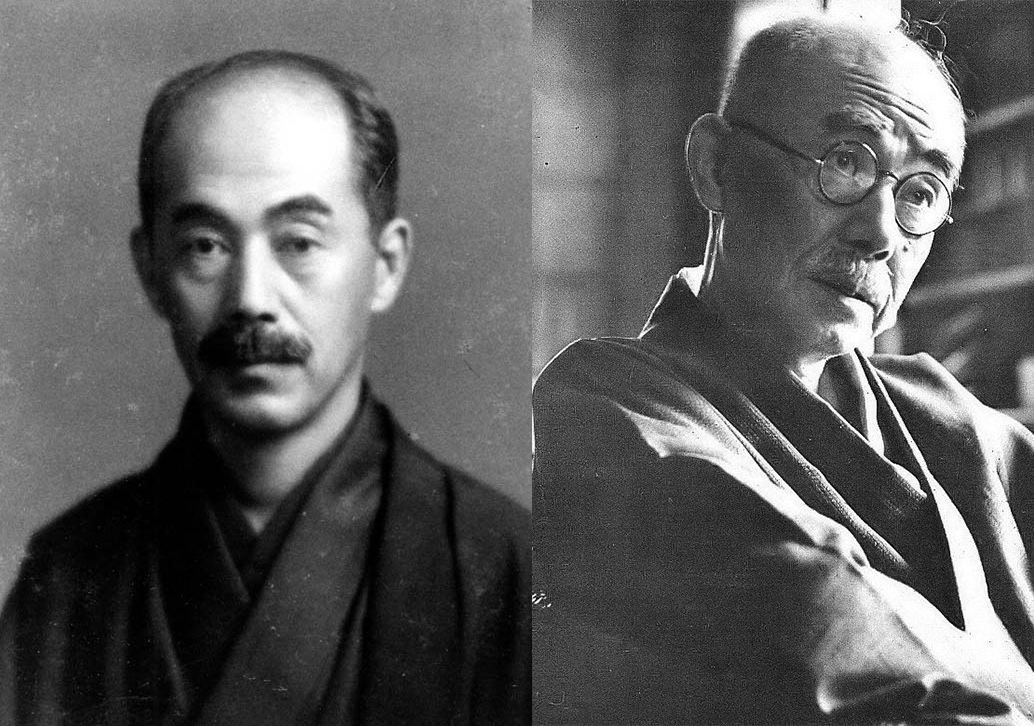

Intellectual discovery is an unparalleled thrill. Being a relatively niche project, finding lore or literature that fits into Neanderthal Paganism like a puzzle piece, even in times of tireless and indulgent curiosity, is rare. For years, I had been aware of Kunio Yanagita as the father of Japanese folklore studies (minzokugaku), famous for first-hand compilations like The Legends of Tōno (1912). Although he remains an obscure figure in the West, bordering on unknown, recent translations of his anthologies have at least earned him a place on the bookshelf for readers of mythology.

I do not remember exactly how I discovered his work—possibly through studying folkloric elements in Hayao Miyazaki’s films—but his out-of-print About Our Ancestors: The Japanese Family System became a constant on my list of rare books to find. It stood out in his bibliography as something broader and more reflective than a collection of folk stories or analyses thereof. I knew there was a possibility that it contained little of interest. But the prospect of an elder folklorist who had walked the countryside recording its living traditions writing directly on the subject of ancestral religion was too compelling to ignore.

It was nowhere to be found online. The only regional copy was held under restricted access in a special collections library. It was only by a chance meeting with an archivist there that I salvaged a chance at getting my hands on this slippery title. Through a combination of persistence and luck—and the archivist’s generous willingness to help— I was able to read, in the comfort of my home, About Our Ancestors two times through, diligently taking notes for future reference. It read in a conversational tone, but with urgency, completely aligned with the essence I hope to capture with Neanderthal Paganism.

Religion in Japan & the Legacy of Kunio Yanagita

Japan’s religious history is defined by the distinctive way foreign forms were absorbed and naturalized. Buddhism, Confucian philosophy, and later Western modernity all reshaped the country’s intellectual life. Yet an older animistic sensibility remained central: the veneration of ancestors, the cyclical return of spirits, and a conception of life and death inseparable from the land. Unlike the West, the indigenous Shinto tradition remains an official major religion of the country.

This endurance did not arise from political unity. For much of its history, Japan functioned as a mosaic of regional clans and dialect areas shaped by mountain, coast, and valley—closer in structure to the Celtic world or pre-colonial North America than to a centralized kingdom. Local customs varied in gesture and tone, yet the great rituals of the year—Bon, New Year, the midsummer and midwinter observances—were recognized across the islands. The result was a mosaic culture: diverse in expression, yet bound by a continuous rhythm of life, death, and return.

The source of this coherence lay not in imperial chronicles or doctrinal institutions, but in the rituals of daily life: household altars, seasonal festivals, funerary customs, and inherited songs. These practices preserved the pre-Buddhist worldview beneath later layers of philosophy and governance. It was this subterranean continuity of spirit that Kunio Yanagita later recognized in his travels. Expecting fragmentation, he found recurring patterns of memory that revealed an unbroken cultural genealogy.

Conflict over the role of Buddhism began early. In the sixth century, a monk sent from Korea proposed its adoption at court, promising diplomatic advantage and cultural prestige. The Soga clan—likely of Korean origin themselves—welcomed the new religion, while rival clans such as Mononobe and Nakatomi opposed it, warning that “the kami (god/deity) of our land will be offended if we worship a foreign kami.” When the Soga gained dominance, Buddhism and Confucian bureaucratic models entered Japan together.

Shōtoku Taishi (574–622), the most prominent Soga-aligned statesman, sponsored temple construction, sent embassies to China, and reshaped administration along continental lines. The Soga held influence for almost a century, and the institutions established under their rule remained in place after their decline. Buddhism had already entered the structure of the state, in part because its temple networks, written doctrine, and hierarchical organization provided a ready-made framework for governance.

Once the Soga were overthrown, to integrate the new faith with ancestral belief, Japanese rulers developed Shinbutsu-shūgo—the alignment of kami and buddhas. Rather than replacing local practices, Buddhism was absorbed into them, its symbols and stories settling into patterns already long established.

For over twelve centuries, this syncretic order shaped Japanese religious life. Gradually, however, Buddhist institutions became entangled with mechanisms of state control. By the Edo period, the danka system required all households to register with Buddhist temples for taxation and surveillance, binding religious identity to state administration.

By then, the prestige of imported systems had begun to dull. The Kokugaku (“National Learning”) scholars of the late Edo era—Motoori Norinaga, Hirata Atsutane, and others—shifted their focus from Chinese classics to ancient Japanese texts. Identity was reframed not as something to be acquired, but remembered. The Meiji Restoration (1868) intensified this shift, forcibly separating Shinto and Buddhism. Years of resentment toward the temple bureaucracy erupted in Haibutsu Kishaku (“abolish Buddhism and destroy Shākyamuni”), a widespread, often locally driven movement that damaged or destroyed tens of thousands of temples and stripped monastic institutions of land and authority. The state then attempted to sculpt a new national identity around mythic Japanese origins.

Yanagita emerged in the generation after this rupture. Yet unlike the Kokugaku scholars before him, he did not attempt to purify Japanese tradition through texts alone. Motoori Norinaga and Hirata Atsutane had turned to ancient literature in search of a pristine origin, but in doing so they relied upon the very Buddhist and Confucian frameworks they hoped to reject. Their vision of Japan remained, in Yanagita’s eyes, a history written from the perspective of court thinkers rather than from the life of the people. Yanagita sought continuity elsewhere: in the living customs of villages, households, and seasonal rites. He believed that the real inheritance of Japan persisted not in scholarly systems but in the practices that had survived quietly, unbroken, in places where doctrine held little sway.

His work marked a shift from antiquarian scholarship to the study of folklore and ethnography—the attempt to understand a culture not by what was said about it, but by what its people continued to do.

About Our Ancestors

Yanagita completed About Our Ancestors in the spring of 1945, while Tokyo burned around him. He was seventy-one. The book reads less like a treatise than a testament: the record of a man who has seen an old world passing and wishes to place something in the hands of those who will inherit whatever remains. It is written in a tone that assumes neither nostalgia nor romanticism, but familiarity—a voice speaking from within a tradition rather than from above it. What he preserves is not the image of Japanese religion found in state shrines or doctrinal systems, but the older order that lived in households and seasonal rites, where the boundary between the living and the dead was porous and continually negotiated.

The central claim is simple: the foundation of Japanese religious life is the ancestor. Many of the gods of shrines and mythic genealogies, Yanagita writes, are ancestral figures whose identities have diffused and expanded across generations—“many other gods are nothing but disguised or forgotten ancestral spirits” (p.6). The household is not merely a grouping of the living but a continuum with the dead. Even when descendants disperse, the family remains conceptually gathered around a single origin, “like petals of a flower with a center” (p.32). The past is not a separate time, but a mode of presence.

This continuity is maintained not through doctrine but through practice. Tradition—dento—is something shown rather than stated, learned through repetition and proximity. It is, Yanagita writes, “handed down to the next generation from what can be ascertained by the ear and eye or something outwardly manifest” (p.40). A tradition persists only as long as it is enacted.

The ritual year expresses this worldview with clarity. New Year and Bon, later separated in tone, were originally variations of the same act: the welcoming of ancestral spirits home (pp.46, 71). Before the turning of the year, houses were swept, purified, and adorned. In some regions, the ancestor returned in the form of Toshi-gami, a kindly elder bringing mochi to renew the household’s vitality—“unless this mochi is eaten, another year cannot be added” (p.59). Bon in midsummer followed the same logic. Fires were lit to guide spirits home and lit again to send them forth. In mountain villages, families led horses into forests to sense the presence of returning ancestors (pp.135–137, 162).

These rites are the lived expression of a cosmology in which the worlds of the living and the dead overlap in ongoing cycles of inheritance, rather than symbols of metaphysical claims.

It is here that the tension with Buddhism becomes visible. Buddhist teaching encourages the dead to depart for other states of existence; the ancestral worldview holds that they remain tied to the land and to the family. The two systems coexisted not by conceptual synthesis but through a layered practice. Priests taught departure, but families continued to welcome return. Yanagita notes that the Buddhist recommendation to “give up their hope of returning to this world” was “not thoroughly accepted” (p.69). Ritual memory proved more durable than philosophical instruction.

Rebirth follows the same inward logic. The spirit does not return into an arbitrary body, nor into a universal cycle without distinction. It returns within its own lineage. One would “surely be reborn to the same kin group and to the same blood line” (pp.174–175). Grandparents reappear in grandchildren; names rotate across generations; a tree planted at a grave may come to signify continuity rather than mere remembrance. Identity is not an individual possession but an intergenerational thread.

By the 1940s, Yanagita feared that the conditions for this continuity were failing. Industrial life drew youth away; the household fractured; festivals narrowed their scope to the recently deceased. “Continuance of the family is a big problem now,” he writes with a quiet directness that would acquire new resonance in the decades that followed (p.178). The question was not merely whether traditions could be preserved, but whether the very structure that sustained memory and gave it legitimacy—the family itself—would continue.

If the line breaks, the relationship between living and dead breaks with it. If the dead are no longer received, they no longer return. And if they no longer return, the world that made their presence intelligible dissolves.

About Our Ancestors is therefore an attempt to articulate the principles of a worldview before they cease to be lived. It assumes the past is not behind us, but alongside us—and remains so only through practice. Without it, Japan’s identity, like so many other modern cultures, would face existential threats different from the air raids that cried over Tokyo—more subtle, and slow.

The worldview Yanagita describes is local in its expression, yet spacious in implication. It belongs to particular villages, households, and seasonal rites, but the structure of thought—the sense of time as cyclical, of ancestry as presence, of the living as stewards of the dead—resonates far beyond Japan.

When we step back, what emerges is not a uniquely Japanese pattern, but a form of human experience that appears in different languages and landscapes. The more closely one studies the rituals of return, inheritance, and seasonal renewal, the more they begin to resemble a shared grammar of belief, shaped by climate, labor, kinship, and memory. Yanagita understood this, even if his work rarely framed it explicitly. His final writings gesture toward a broader horizon, one in which the study of folklore becomes a way of understanding the deep structures of the human world.

The Need for Comparative Study

“The comparative study of folklore still has a long way to go. We think of this comparative study as the final stage of human self-understanding and wait impatiently for the day it will come to maturity.” —Kunio Yanagita, 1962

After the war, Japan entered a period of unusually open cultural exchange with the West. What followed was not replacement or dilution, but a reorganization of expression. The older sensibilities did not disappear; they found new modes of appearance in film, literature, design, and everyday aesthetics. As Japanese culture became increasingly visible beyond its borders, it carried with it a way of seeing shaped over centuries: a world understood as layered with unseen presences, time felt as seasonal and circular rather than linear, memory experienced as something that still participates in the present.

What has become clear in the postwar era is the compatibility of the European and Japanese mind—demonstrated through modern cultural mediums, and indebted in part to our historical overlap in recent centuries—but rooted in a shared inheritance in the deepest sense.

This is exactly what Yanagita suspected when he called the comparative study of folklore “the final stage of human self-understanding.” It is the reason why Hayao Miyazaki’s heroic and deeply folkloric films resonate globally. His worlds are shaped by the same sensibility Yanagita describes: that the land is alive, that the dead return, that the invisible world lies close to the visible one. Certain narrative patterns—the crossing of thresholds, the seasonal return, the coexistence of the living and the dead—belong to no single culture, but to the deeper structure of the human mind.

Our tribal civilizations faced the coming of universal religious systems from top down simultaneously: Buddhism encroaching from China, Christianity from Rome—both fueled by the desire for power and control. In both regions, we lagged behind the sophisticated hive minds and war machines, but were equipped with a spiritual inheritance that could not be cut down or overshadowed—that still, in our rapidly changing world, enjoys unbroken continuity.

In Europe, the old festivals continued under Christian names. In Japan, the kami rites continued beneath Buddhist ones. In both cases, the form shifted while the underlying logic remained. The anthropologist Kuroda has pointed out that what we now call “Shinto” was not originally a distinct religion, but a conceptual framework used to describe localized ritual and ancestor worship within the dominant Buddhist vocabulary. The West has a parallel phenomenon in what might be called “interpreted Europe,” where pre-Christian mythological structures are frequently encountered in texts written by Christian chroniclers, filtered through their metaphysical assumptions and theological boundaries. Both “Shinto” and “Paganism” as labels were invented to differentiate indigenous practices from imported religions.

When we place these worlds side by side, there is clearly a way of understanding life and death that emphasizes return, continuity, kinship, and the land as a vessel of memory. The northern hemisphere developed these patterns under similar environmental and seasonal conditions; the winter-summer cycle, the solstices and equinoxes, the dependence on stored food through dark months, the need for communal ceremony to renew meaning during seasonal scarcity. These conditions shaped religious expression long before Buddhism or Christianity arrived.

Yanagita believed that continuity was not sustained through ideology or state power, but through the ongoing relationship between the living and the dead. A culture persists when the living understand themselves as belonging to a lineage rather than standing alone. The form of the household may change, the rites may simplify, but the idea that the past remains present through us is what allows a tradition to remain alive.

We are only beginning to understand how deep this inheritance runs. The similarities between distant ritual traditions—between the Japanese summer fires that welcome the ancestors and the midsummer bonfires of Europe, between the household altar and the remembrance of the dead at the family hearth, between the return of Toshi-gami and the ancestral visitations of the Celtic year—suggest not coincidence, but memory. A memory older than organized religion, older than imperial systems, older than writing. It is carried in seasonal rhythms, in the instinct to speak to the dead as if they still listen, in the understanding that the land remembers those who have walked it. To study these worlds side by side is not to collapse them into sameness, but to recognize that both are branches of an ancient root—an inheritance of the northern world carried forward through the long passage of time.

Our task now is not to reconstruct what has been lost, nor to return to an imagined past, but to learn to recognize the shape of inheritance when it appears, to tend it where it still lives, and to remember that we stand inside a story far older than ourselves.

Works Cited & Further Reading

The Japanese Experience: A Short Story of Japan by W.G. Beasley (1999)

About Our Ancestors: The Japanese Family System by Kunio Yanagita*

Links

Kokogaku (“national learning” academic movement)

Shinbutsu Bunri (Separation of Buddhism and Shinto)

Shinbutsu Shugo (Syncretization of Buddhism and Shinto)

*For those interested in reading About Our Ancestors directly, I have uploaded my scans to the Internet Archive for preservation and study here.

Thank you!

Hail the Ancestors!!!!

Beautifully written; a sensitive flow of lineage.