Why Did Neanderthals Worship the Bear?

Neanderthals honored the bear in ways we can still recognize. We’ve been carrying that reverence for 50,000 years.

There isn’t another animal more feared or surrounded by mythology than the bear. Not only does the bear dominate the skies as the preeminent constellation—it has remained a symbolic cornerstone across the northern hemisphere as far back as archaeology can reach. The archetype of the bear remains in characters and customs still prominent in our own culture—often unbeknownst to us. Just like our DNA, “bear worship” can be traced back to Neanderthals, where the first religious impulses murmured in the caves of Paleolithic Eurasia.

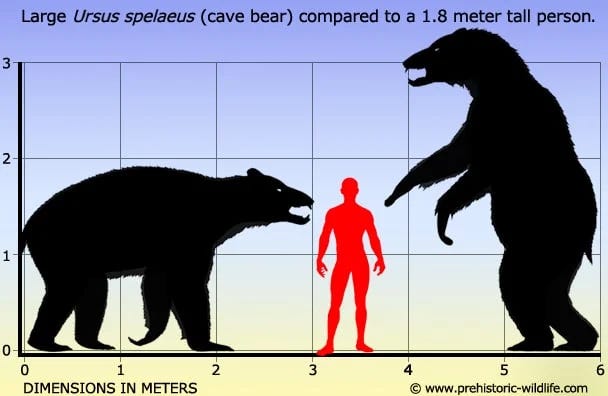

In the Ice Age north, the cave bear (Ursus spelaeus) and the even larger short-faced bear (Arctodus simus) were immense predators, heavier than any modern bear and towering over a man on its hind legs. Whether it was these extinct giants or the surviving subspecies, they lived where humans lived, roamed where humans roamed, and in winter vanished into the earth, breathing but unseen.

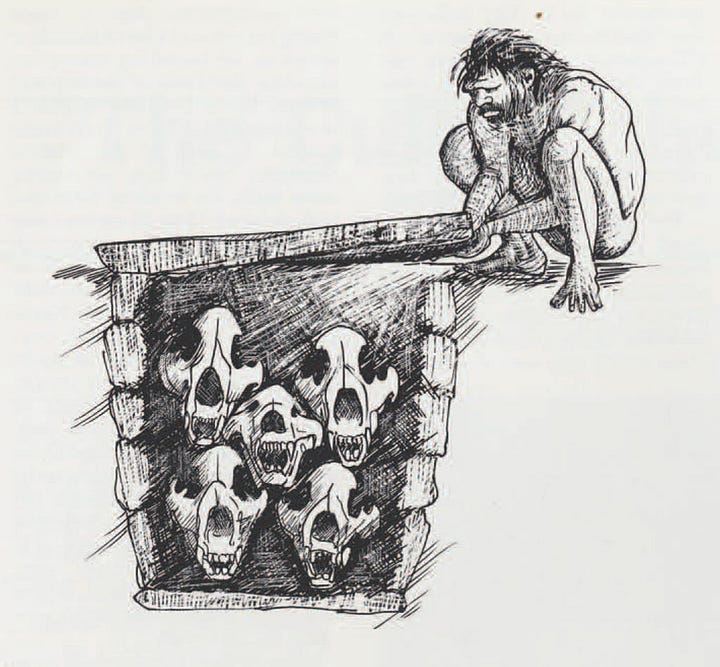

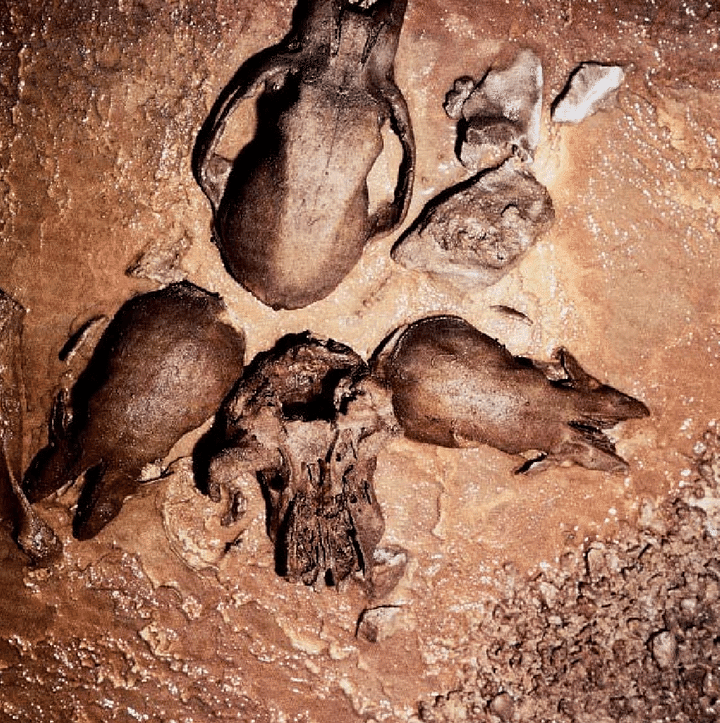

The first clear argument for a Paleolithic bear cult came from Swiss archaeologist Emil Bächler. In the early 20th century, while excavating Drachenloch cave, he uncovered stone-lined niches holding cave bear skulls, some neatly arranged as if for display. At Regourdou in France, a Neanderthal was buried alongside bear bones and stone tools. In Chauvet, famous for its painted lions and mammoths, cave bear claw marks run across the walls—even over some of the oldest art. The pattern is hard to ignore: repeated, deliberate encounters with the bear, and signs that its remains were treated with special care.

But why the bear? Why single out this animal, among all the great beasts of the Pleistocene, for such treatment?

Part of the answer lies in resemblance. Bears and humans share unusual traits: both can stand upright, use their forelimbs with dexterity, and eat a wide variety of foods—berries, roots, fish, and meat. Their forward-facing eyes and broad faces echo our own. They are intelligent, curious, and even playful. They also rear their young for an unusually long time compared to most mammals, with cubs staying close to their mothers for over two years. The image of a mother bear carrying her young on her back would have been as familiar then as now. Our verb to bear—to carry—comes from this act. The constellation Ursa Major, “the Great Bear,” also known as the Wagon, recalls both the mother’s burden and the mythic figure of Atlas bearing the weight of the world. Many Native American tribes called the bear “half-human,” a man without fire or ancestors, and some refused to eat its meat, considering it a form of cannibalism.

“Bears are strange animals, and often act in such a human way that one is tempted to credit them with a considerable reasoning power.” —Don Hitchcock

But resemblance alone doesn’t explain reverence. The bear’s life cycle mirrors the northern year. In autumn, as the sun weakens, it retreats into the earth. In midwinter—at the very moment of the sun’s rebirth at the solstice—bear cubs are born in the dark. By spring, mother and young emerge, just as the land renews itself. Bears could also be dangerous: short-sighted, fiercely protective, and, in the case of males, known to kill cubs that weren’t their own. These traits, remembered and retold, may have helped shape the ogres, witches, and man-eaters of later folklore.

This rhythm still runs through our traditions. Halloween, the last feast before the dark, has us fattening ourselves for winter with sweets—something bears instinctively do before their long sleep. The birth of Christ at the Winter Solstice, the sun’s return to the world, coincides with the birth of cubs in the den. By Easter, the bear emerges from the cave, as Christ from the tomb, both marking the triumph of life over death.

Some archaeologists have gone further, suggesting the bear figured into initiation rites. In Montespan Cave in France, the clay body of a bear was found, head missing but torso marked with holes as if from spears. In other caves, painted animals seem to move in the flicker of a torch—an effect only visible to those deep inside. Perhaps young initiates were led into that shifting darkness to face the image or presence of the bear. Emerging afterward would have been a symbolic rebirth—especially through the narrow ravines of caves like Bruniquel and Drachenloch—into the community, echoing the bear’s return from hibernation.

Bear worship is not some alien relic from a vanished world. Neanderthals are our ancestors, and their reverence for the bear is part of our inheritance. David Rockwell notes that “Native North Americans, European, and Asians possessed strikingly similar bear-hunting rituals—they used the same circumlocutions to address bears before and during their hunts, they used the same weapons to kill the animals, they decorated the carcasses in similar ways, they observed similar restrictions when they ate bear meat, and they disposed of the bones in the same way” (xii). The careful placing of a skull in a dark cave may seem strange to us now, but its meaning remains close: recognition of kinship, marking the year’s turning, hoping for renewal. The bear helped shape the beliefs of those who came before us, and because of them, it has shaped the rhythm of our spiritual life since.

Further Reading & Sources

The Sacred Paw: The Bear in Nature, Myth, and Literature by Paul Shepard and Barry Sanders

The Great Mother by Eric Neumann

The Secret of the She-Bear: An unexpected key to understand European mythologies, traditions and tales by Marie Cachet

Giving Voice to Bear: North American Indian Myths, Rituals, and Images of the Bear by David Rockwell

The Bear and Cave Bear in Fact, Myth, and Legend by Don Hitchcock

An interesting parallel between the exit from the cave and the tomb around Easter

Check out the bear festival in Romania. https://apimagesblog.com/blog/2023/1/16/bear-costumes-dance-at-popular-romanian-festival

A light version of this (more just as a travelling circus attraction around the holidays) is somehow entertained in all the big cities. But in some places they still have the real deal.

I remember also parading a live bear lead by a ring through its nose on these occasions, bit this practice faded out with the animal abuse organizations clamping down on it.

On a lighter note I remember a firecamp song going about how a she bear stole a girl from a group of mountaineers and they haggle to get her back. I'm sure there is a deep root for this too. Lots of connections to be made.