Did Neanderthals Influence Christianity?

Archetypes of Death and Renewal from the Ice Age to the Gospels

“The Christ-symbol is as much a product of the collective unconscious as it is of history.” —Carl Jung

The story of Christ did not arise in a vacuum. However singular its claims, the symbolic grammar in which it is written—the tomb and its resurrection, the sacred meal, the promise of light breaking into darkness—long predates the first century. These are not random inventions of the Near East, nor mere borrowings from Hellenistic cults. They belong to a lineage of religious thought as old as humanity itself, shaped first in the mind of Paleolithic man and carried forward through millennia of myth.

Much has been made of Christianity’s “pagan roots”: its festivals coinciding with solstices, its echoes of various world mythologies, its moral laws overlapping with older codes. To understand its deeper ancestry, we will return not to Athens or Babylon but to the Ice Age, where Neanderthals began enacting the symbolic dramas that would structure religion for hundreds of thousands of years.

The Resurrection

The cave was humanity’s first cathedral. Its darkness was not a shelter for daily life but a chamber reserved for ritual, for marking thresholds between death and life. Archaeologists at Shanidar, Drachenloch, and Regourdou have uncovered Neanderthal burials where bodies were carefully arranged: some curled into fetal positions, others dusted with red ochre — a pigment long associated with blood and renewal. Many were oriented east to west, mirroring the path of the sun. In the same chambers, cave bear skulls were set in niches, sometimes beside the dead. These details suggest a symbolic logic: the cave as both womb and tomb, death as a passage, and the promise of return in another form.

The choice of the bear is telling. Unlike herd animals hunted for food, the bear is a solitary creature that withdraws into the earth in winter, only to re-emerge in spring with her cubs. She is both a fearsome predator and nurturing mother, embodying death and renewal in a single form. To organize bear skulls in caves was to stage a ritual drama of hibernation, rebirth, and ancestral return. In the Paleolithic imagination, the cave was the cosmic womb, and the bear was its herald of resurrection.

Marie Cachet has suggested in The Secret of the She-Bear that caves also served as sites of initiation. She points to the famous Chauvet footprints, where a child’s bare steps are preserved beside those of a wolf-dog. The image is striking: the young initiate accompanied into darkness by a guide, leading him through the liminal space of death and rebirth. Such a descent was not for shelter but for transformation. To enter the cave was to enter death symbolically, to emerge reborn into the community with a new name as if resurrected.

In ancient times, science and ritual were interwoven. The reality of ancestral reincarnation—a child embodying the features and spirit of forebears—was mirrored in initiation rites that enacted a symbolic death and rebirth when the child came of age. The cycle of the bear, the return of the sun at solstice, and the rhythm of the seasons were all folded into this archetype of renewal.

This logic flowed outward through the ages. Orpheus descends into the underworld to rescue his other half, his beloved. (In his book Carnaval, René Gaignabet insists that Orpheus’ descent into the underworld and his eventual successful return represent a model borrowed and adapted from prehistoric bear ceremonies. In Christianity, Christ’s descent into hell mimics Orpheus and thus the bear.) Dionysus is torn apart and restored, observed in subterranean rites that promised renewal. Osiris is slain and dismembered, reassembled and enthroned as lord, his cycle ritually reenacted each year along the Nile as a promise of resurrection. Mithras springs from the rock, his cult gathered in cave-temples to feast by torchlight. Each figure replays the same sequence: descent, concealment, trial, and re-emergence—changed, renewed, or exalted.

Christianity takes up the symbol with extraordinary clarity. Christ is placed in the cave of death and rises into life. Tradition locates his nativity in a grotto, bookending his story in the same archetypal chamber. His resurrection is not an invention isolated in history but the flowering of the oldest ritual insight: that death, entered into fully, can open onto life transfigured.

The Sacred Meal and Sacrifice

If the cave was the first cathedral, the meal was its first liturgy. Across Paleolithic sites, animal remains in ritual contexts suggest that eating was not only a matter of sustenance, but also a means of social interaction and expression. Feasting together was a way of binding the living to the cycle of death and renewal, a communion with the sacred through the life that had been taken. In sharing the body of the animal, early humans made its vitality their own, transforming consumption into ritual.

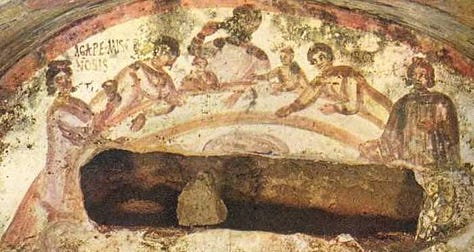

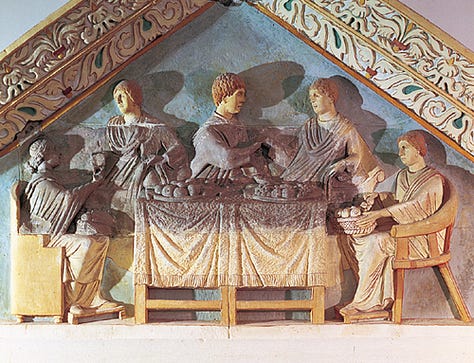

This archetype carried forward into the ancient world. The followers of Dionysus consumed raw flesh in omophagic rites of divine participation, while Orphic initiates drank wine as the blood of the god. Egyptian worshipers of Osiris partook of bread and beer that represented his dismembered body restored to life, dramatizing both death and renewal through consumption. Among Greeks and Romans, funerary meals were shared at tombs in a refrigerium, blurring the line between the living and the dead as food was offered in common. In each case, the act of eating together was not mere nourishment but a symbolic sharing in death, and through it, in renewed life.

Christianity inherited this structure and transfigured it. The Last Supper, remembered in the Eucharist, is the sacred meal of sacrifice universalized. Bread becomes body, wine becomes blood; but no longer the seasonal flesh of an animal, nor the esoteric rite of an initiate. Instead, the sacrifice is Christ himself, offered once for all, and the meal is open to all who believe. The pattern is ancient, but its fulfillment is distinctive: a ritual of death and renewal that binds not only a tribe or cult, but the entire communion of the faithful.

Light in Darkness

From the beginning, humans sought light in dark places: torches carried through narrow cave passageways, pressed against walls to draw animals that leapt by flicker. In these chambers of ritual darkness, flame was a symbol of eternal life. The cave became a theatre of illumination, where light itself was a sign of life breaking into shadow.

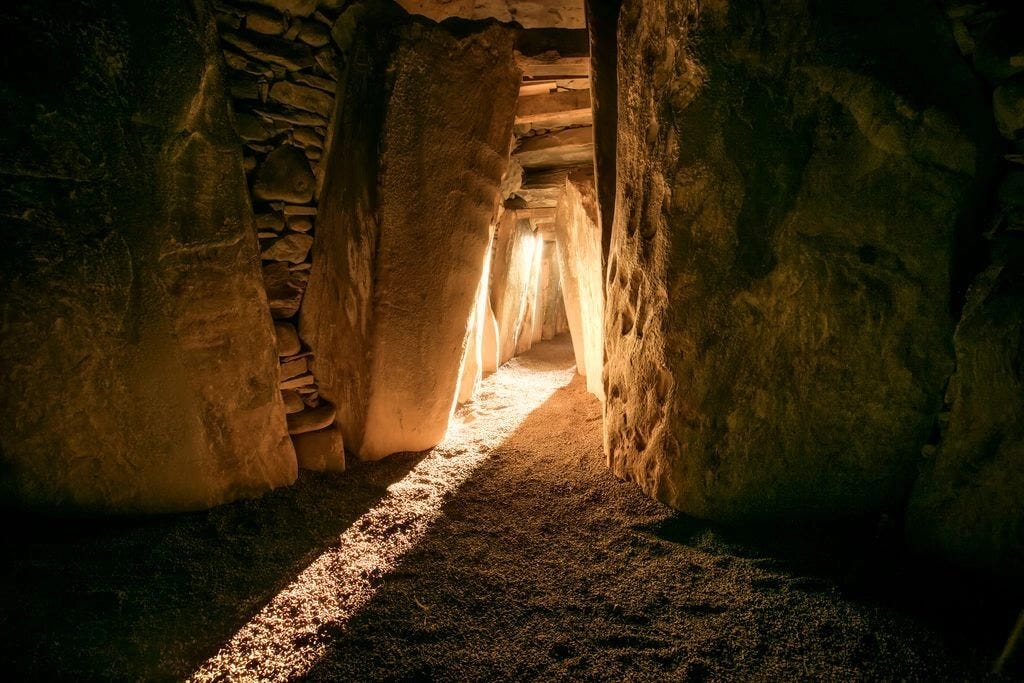

This logic extended outward into the landscape. In the Neolithic, megalithic tombs and dolmens—architectural descendants of the cave—were carefully aligned with the solstices. At Newgrange in Ireland, built more than 5,000 years ago, the midwinter sunrise pierces a narrow passage to flood the inner chamber with light. Across Eurasia, similar structures were oriented so that the first light of the solstice penetrated the tomb, dramatizing the sun's rebirth in the house of the dead. The cave had become a built stone structure, and the ancient drama of darkness and dawn was staged anew.

From these alignments, it is clear that the sun itself was a central figure in prehistoric religion. Its annual renewal at the winter solstice, its daily arc across the heavens—these were woven into myths of dying and rising gods. Solar deities are prominent in countless traditions: Helios and Apollo in Greece, Sol Invictus in Rome, Mithras born on December 25th, and other gods who embodied renewal. Each transposed into myth what had been enacted ritually in the darkness of caves and the alignment of tombs.

Christianity entered this symbolic field already thick with meaning. To proclaim Christ as the “light of the world” was to speak in a language humanity had been rehearsing for millennia. His birth three days after the winter solstice was not a coincidence but a continuation of an age-old tradition. The moment of deepest dark had always been the threshold of renewal. The Prologue of John gives this ancient image its fullest voice: the light shines in the darkness, and the darkness has not overcome it.

The Trinity

“Augustine received the Christian doctrine of the trinity from the Pagan philosopher Plotinus (c. 205-270 c.e.), who ‘fed his mind on the attributes of the Pagan divinities and was steeped in Hellenistic rational religion and esotericism.’” —Tom Harpur

Before doctrine, there is pattern. Much of prehistoric ritual moves in threes: life, death, return; day, night, dawn; autumn’s fading, winter’s hidden interval, and spring’s renewal. The cave section already implies such a rhythm—entrance, sojourn, emergence—staged in darkness with fire and companions. Even if there is no written Neanderthal “theology of three,” the dramaturgy of rebirth they enacted naturally falls into a triadic arc.

Later Stone Age monuments make the motif visible in stone. Passage graves and carved rocks across Atlantic Europe favor triple motifs—especially the triple spiral at Brú na Bóinne—where a single sign turns upon itself three times, like a diagram of return. Their meanings are opaque; what is clear is recurrence. The builders repeatedly inscribed a rhythm in which a path goes out, turns, and comes back changed. The threefold mark is a way to draw renewal.

Greek number-philosophy later treats three as the first complete number: one proposes, two divides, three resolves. Pythagorean writers considered the triangle to be the first figure; harmony itself was described as small ratios that come in threes. Without forcing lines of descent, it is enough to say that Mediterranean intellectual culture found a natural language for completeness in the principle of three, an outlook that would shape the way later Christians expressed their experience of God.

Rites of passage give the old rhythm a vocabulary: separation, liminality, incorporation. An initiate is led away, challenged in some dramatic way, then restored to the community in a new state. Read through this lens, the Paleolithic descent becomes a textbook triad: the child steps from daylight into the earth, remains under guidance in the chamber where the people face death, and returns as someone else. The same rhythm shaped the Eleusinian Mysteries, which unfolded in descent, search, and ascent—culminating not in return to the ordinary, but in an exalted vision of renewal. Mythic narrative preserves the pattern as well: trials often come in threes, and the hero’s journey reaches fulfillment not on the second attempt but on the third.

Christianity follows the same logic: the descent into death, the harrowing of the underworld, and finally the ascent—resurrection and ascension—as the decisive third act. This structure itself proved to be the simplest and most enduring map for transformation.

The baptismal and doxological name of the Christian Trinity presents one life expressed in threefold form: Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. The form is metaphysical, not merely symbolic, yet it is a form the human imagination already knows how to carry. A world that has long rehearsed transformation in threes will not stumble over a mystery expressed as a Trinity. It will feel, at some deep level, like a true shape for the thing being said.

If caves taught early humans to move from death through a middle night into renewed life, and if philosophers treated three as the mark of wholeness, then the Christian Trinity arrived in minds already prepared. The proclamation of one God in a threefold life could therefore take root in imaginations trained, for ages, that the journey of transformation has, from the beginning, unfolded in three acts.

Morality

Some might object that Christian symbols cannot be traced back to caves and bears because they are not merely natural metaphors. They are a moral vision, a revelation of divine love—more than the cycle of seasons and the fear of death. Neanderthals and their descendants may have mirrored natural rhythms, but they did not proclaim commandments or absolve man of his inherent flaws.

The distinction is legitimate, but symbols do not become less powerful when they are joined to ethics; they become more so. Christianity is unique not because it invented the cave, the meal, the light, or the threefold pattern, but because it bound those ancient archetypes to a moral and spiritual vision of sacrifice and salvation. As Joseph Henderson observed in Man and His Symbols, “In contrast with the [pagan] central focus on nature’s eternal cycle of birth and death, the Christian mystery points forward to the initiate’s ultimate hope of union with a transcendent god” (139–40). Where the Paleolithic imagination saw in the cave the promise of return, Christ filled that promise in exchange for devotion to Him. Where the sacred meal once dramatized the bond between man and his surroundings, Christianity made it a communion with God.

In this sense, the moral code of the faith did not displace the old archetypes but inhabited them, giving their deep familiarity new weight. It resonates not because it invented a new language, but because it spoke in one already etched into human experience. To see this lineage apart from the political history of the church helps explain its endurance. A moral vision of love and salvation found its body in symbols that were already millennia old. That marriage of the eternal and the archaic is why, when the story is told, the human spirit still recognizes itself.

maybe we learned to partake in rituals and tell complex stories through those rituals from our brother and sister hominid species wherever we ended up. maybe we influenced their culture and vice versa. everyone likes a yarn. we developed the capacity for language alongside them and we shared stories and rituals together in deep time.

A superb piece of writing. Interesting to think that the light shining into New Grange could easily be seen as a deity. Today, Gods are rarely imagined as underworld Gods, and as we fill our lives and cities with light from screens, street lamps, cars, and modern mirrors, we have become less spiritual in the modern world. Churches today still rely on dark recesses and candles, reflecting the impression of a cave. Here's to more darkness!