Flower Power: Neanderthals Revitalized in Pop Culture

How the hippie movement helped reinvent the Neanderthal

"Little flower — but if I could understand

What you are, root and all, and all in all,

I should know what God and man is."

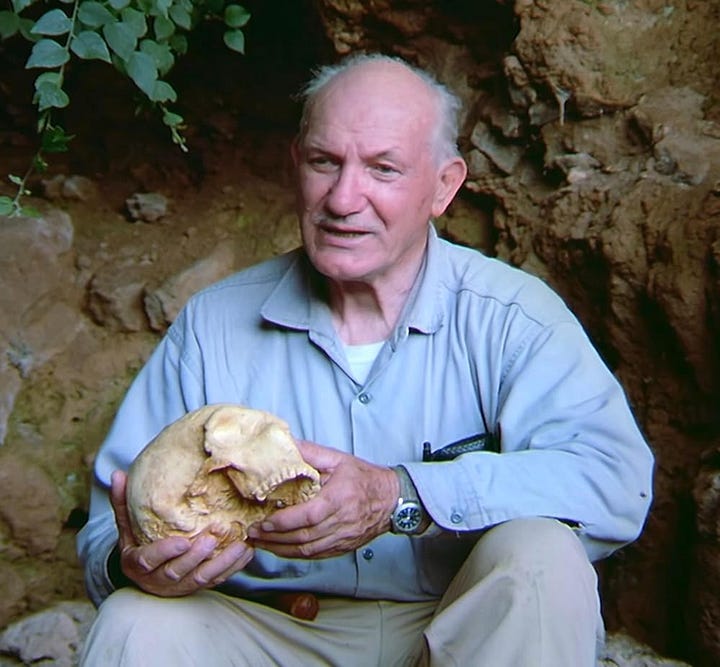

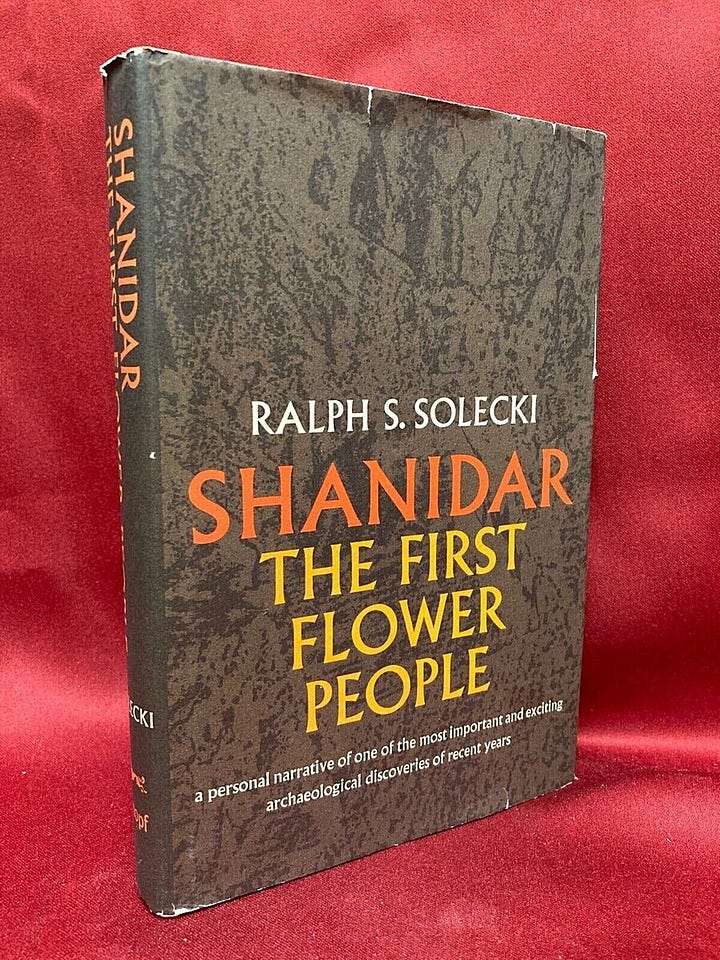

From a young age, Ralph Solecki independently traversed his home state of New York for remnants from the lands’ original tribal inhabitants. After serving America in Europe during World War II from 1942 to 1945, he pursued anthropology at Columbia University. Along with his wife and fellow archaeologist Rose, he traveled to the Levant in 1953 to find more clues to bygone eras of humanity. At Shanidar Cave in the Zagros Mountains of Northern Iraq, they uncovered a series of Neanderthal skeletons that would strengthen, and in some cases establish, the bond between us and our Paleolithic ancestors. Solecki’s analysis, culminating in the 1971 book The First Flower People, was the first of its kind – a book on Neanderthal archaeology marketed towards a popular audience. Because of his ability to capitalize on public consciousness, his legacy is solidified for daring to attribute a new level of intelligence, soul, and empathy to Neanderthals.

The decades following the war affected every aspect of Western society. An economic boom gave birth to a forward-thinking generation that set new trajectories in technology, academia, the arts, and science. As new perspectives emerged across the disciplinary landscape, Solecki detailed his seven-year-long excavation of Shanidar Cave. He saw parallels between Neanderthals and the hippie movement, which captured the imagination of young people in America.

The publishing of The First Flower People conveniently aligned with the solidification of hippiedom in the popular zeitgeist. Hippies were initially known primarily for ‘dropping out’ from the expectations of their conservative, industrious upbringing to embrace down-to-earth communal living. The early Californian hippies (who spawned from young immigrants from Germany, where the first Neanderthal was discovered a hundred years earlier) were referred to as “flower children” for their free-flowing, naturalistic attitude and appearance. One of the most famous images from the era’s peace demonstrations shows a young woman placing a flower inside the barrel of a policeman’s rifle.

The goal of the original hippies was a return to nature – cultivating simpler lives as an alternative to the fast-paced civilization of the post-war metropolis and emerging suburbs. By the late 1960’s, hippiedom had become a widespread trend, and the combination of openness to new ideas and the desire to get back to the land was a stylish approach to life.

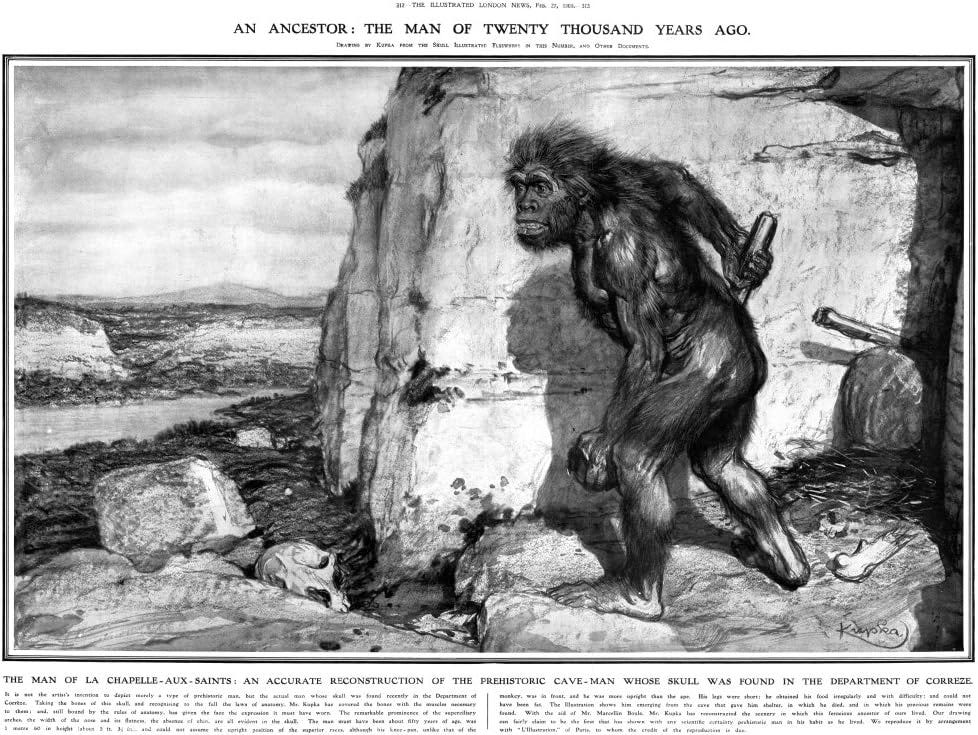

What could be more ‘hippie,’ Solecki figured, than Stone Age man? His tribal existence and handiness with natural materials could be compared to the ideal hippie commune. Neanderthals could be repositioned into a positive light for presentation to a new generation. Their lack of a physical legacy, which until that point was considered evidence for a lack of intelligence, could now be called the manifestation of a collective ‘leave-no-trace’ philosophy – the ultimate sustainable approach to man’s life on Earth. With evidence for altruism and sensitive, creative behavior, the generation that prided itself on open-mindedness would be the perfect audience for the soulful Neanderthal pitch. Along with paleobotanist Arlette Leroi-Gourhan (wife of André Leroi-Gourhan, who was skeptical of Neanderthal intelligence), Solecki ventured to counteract Marcellin Boule’s speculative depiction of the knuckle-dragging Neanderthal that had dominated the public and academic consciousness for a century.

“It was originally a Frenchman, Boule, who is credited with the bestial characterization of the Neanderthals. And it was a Frenchwoman, Mme. Leroi-Gourhan, who gave us the soft touch. The observation has been made that the Neanderthal has been ridiculed and rejected, but despite this, according to all the proofs that can be mustered, he is still our ancestor.”1

Regardless of the various discoveries made in the first half of the twentieth century, they all lead to Solecki’s book that captured the publics’ imagination by being the right discovery and message at the right time. Considering the philosophical reform that defined the period, Neanderthal perception was due for a shift in trajectory – and Solecki was the one to initiate it.

Major Findings and Analysis

The remains of five different individuals were uncovered during Solecki’s tenure at the Shanidar – the most notable of which are Shanidar 1 and Shanidar 4 – both dated to approximately 40,000 years ago, with the oldest skeleton dated to 60,000 years ago.

Analysis of Shanidar 1 reveals an individual who suffered physically throughout his life, but whose life-threatening injuries ultimately healed before his death. Hypotheses surrounding the specifics of his injuries have varied, but what’s certain is that the individual suffered severe head trauma and damage to the body. He would have required assistance to survive in a primitive setting. These circumstances point to two possibilities that are not mutually exclusive but are equally novel at this point in Neanderthal research – healthcare and charity.

Discovered in 1960 during the fourth wave of excavations, Shanidar 4 brought fame to the site and become the focal point of Solecki’s life’s work. Soil samples from the grave submitted to Mme. Leroi-Gourhan showed clusters of as much as 100 pollen grains from 7 species of flowers, giving birth to the theory that Neanderthals had adorned the dead body with freshly picked flowers of a small and brightly-colored variety, known as the “flower burial theory.” Leroi-Gourhan concluded that bunches of complete flowers had been introduced into the cave by men, noting that their placement in relation to the entrance of the cave suggests that “neither birds, nor rodents, nor the presence of mammalian coprolites can explain [their] presence.” Solecki echoed: “Animals could [not] have carried flowers in such a manner in the first place, and the second, they could not have deposited them with a burial.”

“One species of flower, the hollyhock, a very large, pretty flower, grows in separate, individual stands. Therefore [Leroi-Gourhan] concluded that someone in the last Ice Age had ranged the mountainside in the mournful task of collecting flowers. The soils from the area immediately bordering the grave did not yield any evidence of flowers. This provided an additional check on the finds.”2

Leroi-Gourhan also noted small pieces of wood added to the grave for some purpose other than fire, and the wing of a butterfly that had perhaps been ornamentally placed along with the flower bunches, all of which had been preserved over the millennia thanks to the stone enclosure around the grave. In contrast to other soil samples that show various isolated pollen grains, the highlighted samples stood out in their cluster formation in such a way that suggest anthropogenic origin.3

Interestingly, flowers including bachelor’s-button, hollyhock, yellow-flowering groundsel, and yarrow, all found among the burial clusters, are known for their medicinal properties, pointing to a possible utilization of herbal remedies, perhaps for cases like Shanidar 1. Solecki himself didn’t fully endorse this possibility, writing that “it would be asking too much to believe that the Neanderthals were cognizant of the medicinal properties of flowers.” Grape hyacinth, also found in clusters around the burial, is purely ornamental.

Later discoveries revived this aspect of the Shanidar findings. In the 2010’s, Karen Hardy of the Catalan Institution for Research and Advanced Studies in Spain and Stephen Buckley of the University of York in the United Kingdom chemically analyzed microorganisms found in the teeth, respiratory and gastrointestinal tracts of Neanderthals from El Sidrón cave in Spain and Spy cave in Belgium, proving that Neanderthals consumed medicinal plants including yarrow and chamomile forty to fifty thousand years ago,4 within the timeframe of when the Shanidar Neanderthals existed:

“One of the most surprising finds was in a Neanderthal from El Sidrón, who suffered from a dental abscess visible on the jawbone. The plaque showed that he also had an intestinal parasite that causes acute diarrhea, so clearly he was quite sick. He was eating poplar, which contains the pain killer salicylic acid (the active ingredient of aspirin), and we could also detect a natural antibiotic mold (Penicillium).

‘Identifying now the bacteria which caused his dental abscess and stomach pains confirm the results we obtained in our study. There is no doubt that the Neanderthals used plants to treat illnesses, and it also demonstrates once again that they had detailed knowledge of their surroundings and the ability to use plants in a variety of ways.’

‘Apparently, Neanderthals possessed a good knowledge of medicinal plants and their various anti-inflammatory and pain-relieving properties, and seem to be self-medicating. The use of antibiotics would be very surprising, as this is more than 40,000 years before we developed penicillin. Certainly our findings contrast markedly with the rather simplistic view of our ancient relatives in popular imagination.’”5

In 2016, a study was published in the National Library of Medicine documenting the litany of accumulated instances of similar discoveries. They amassed “61 different taxa from 26 different plant families found at 17 different archaeological sites” all pointing to nutritional, medicinal, and ritual use of plants.6 In 1982, the Hŭngsu Child was discovered on the Korean peninsula with traces of pollen and flowers underneath soil where it had been buried during the same era as Shanidar 4. Although classified as a Homo Sapien, it reaffirms the idea of humans being capable of a soulful tribute for the dead 40,000 years ago. The Red Lady of El Mirón, a skeleton from the Upper Paleolithic, had also been covered in flowers, and the origins of these flowers have not since been brought into question as Shanidar 4 eventually was.

Unlike the arrangement of bear skulls and femurs at Drachenloch and Le Regourdou, flowers on a grave are familiar to the modern mind, demonstrating empathy and appreciation for beauty that had until that point not been attributed to Neanderthals. Functionally speaking, the practice exists in the same vein as painting skeletons with red ochre, a blood symbol, or burying bodies in the fetal position – these are symbols expressed with rebirth in mind. Mme. Leroi-Gourhan figured that the Shanidar flowers would have been picked in late Spring around May, meaning they were freshly bloomed and at their peak of depicting the beauty and sensitivity of new life.

The flower burial theory has maintained notoriety since the publication of The First Flower People, overcoming the pitfalls of Arthur Keith’s proposed intelligent Neanderthal (“not in the gorilla stage”) and Emil Bächler’s bear cult theory which have contrastingly fallen into relative obscurity. Although 1971 didn't completely flip the script, Solecki’s work remains a beacon of hope that Neanderthals weren’t so stupid after all.

Criticism

The First Flower People echoed the idealism of the early 1960’s. When that idealism failed to become reality, the backlash left a lasting mark. Not only was a generation thrown into a tailspin of divorce, alienation, excess, and spiritual obscurity, but the supposedly unprejudiced basis on which many academics began their careers lacked the foundation of the establishment they were inheriting. Ironically their tenure became more assertive in its convictions, less open to new ideas, and has catalyzed a rift between academia and the public that is still growing.

For the Neanderthal question, this meant a return to conservative skepticism. In 1999, Jeffrey Sommer published “A Re-evaluation of Neanderthal Burial Ritual” in the Cambridge Archaeological Journal, bringing the flower burial theory into question. Sommer’s claim is that rodents (specifically Meriones persicus, the Persian jird) piled the flowers in clusters instead of Neanderthals:

“Richard Redding excavated several burrows of the closely related species Meriones crassus, and found large numbers of flower heads, including members of the Compositae family, stored in the side tunnels of the burrows. The number of flower heads these rodents had saved was more than enough to account for the pollen found near Shanidar IV. Indeed, the habit of storing nesting material and/or food, including seeds, flower heads, leaves, and other vegetal material in their burrow is common within the genus Meriones.”

There is no specification, however, of the plants identified. Yarrow, for example, is often used as a repellent for rodent species within the Muridae family and was one of the more prominent flowers identified within the Shanidar IV burial. Would it be reasonable to expect that a rodent species with an aversion to pungent herbs to be burrowing it within its own nest?

In 2015, Marta Fiacconi and Chris Hunt published a study of the pollen taphonomy at Shanidar, taking account of Leroi-Gourhan’s work as well as Sommer’s. They suggest that bees could have been responsible for carrying in some of the pollen, especially toward the rear of the cave if they happened to reside there temporarily (although, why bees would be carrying significant amounts of pollen into a cave, I’m not sure).

Less hardline than Sommer’s critique, the study grants the possibility of rodent involvement “account[ing] for some of the vegetal matter around Shanidar 4,”7 as well as that of Solecki and Leroi-Gourhan’s original theory, since the concentrations are significantly most heavy at the burial site. Plus, by 2015, Neanderthal intelligence had been more concretely established in a way that it wasn’t when Sommer published his argument.

2016 Excavation and Shanidar Z

The Caucasus region to the Levant has become vital for Neanderthal archaeology outside of Europe, with southern Palestine and Northeast Iran in the Zagros region marking the far ends of the Neanderthal range to the south and east respectively. It is currently the only region where pure Neanderthal and Cro-Magnon remains have been found together, making the region likely where the first admixture between Neanderthals and Homo Sapiens took place approximately 40,000 years ago. Being in the middle of ongoing political unrest and military conflict, opportunities for excavations have been scarce and caused Solecki’s work in the region to be interrupted and ultimately cut short.

In 2016, the latest wave of excavations at Shanidar revealed a skeleton called Shanidar Z. Its discovery “suggests there is still more funerary mystery left in the cave” according to Emma Pomeroy of the University of Cambridge who led excavations and wrote the 2020 study after initial analyses. She concluded “strong evidence that Shanidar Z was deliberately buried” considering its adjacency to Shanidar 4. What her team discovered was that the pit in which Shanidar 4 and Z were both found was likely dug on purpose – the main question that remained was whether the bodies were buried simultaneously, or if it was a spot that was continually returned to. In the study, Pomeroy notes a triangular-shaped rock by its “morphological and locational distinctiveness” that could have been positioned by Neanderthals to identify the burial site, most likely under the head of Shanidar 4. Shanidar Z was eventually dated as older than 70,000 years, making it significantly older than Shanidar 4, supporting the proposition that the site had been continually used for burial by multiple generations.8

By the time Shanidar Z made its mark throughout academia, even hesitant minds began to fold under the weight of evidence. Pomeroy said in 2020, “from initially being a skeptic based on many of the other published critiques of the flower-burial evidence, I am coming round to think this scenario is much more plausible.”9

Solecki’s Legacy

The back-and-forth of this debate is exemplary of the resistance to Neanderthal intelligence. Today, it is uncommon to see the flower burial theory mentioned without the caveat of it having been disproven, even following the 2016 Shanidar Z study and other evidence of symbolic culture. Persistently, since the earliest interpretations of Neanderthals, we’ve demonstrated the need to keep them in a degree of magnitude under us, seemingly unable to grant this “archaic species” the ability to be empathetic or sophisticated in any significant way. Although academia has come around somewhat, it remains persistent in its disbelief that modern people have anything to learn from this species that we’ve left behind on the evolutionary ladder.

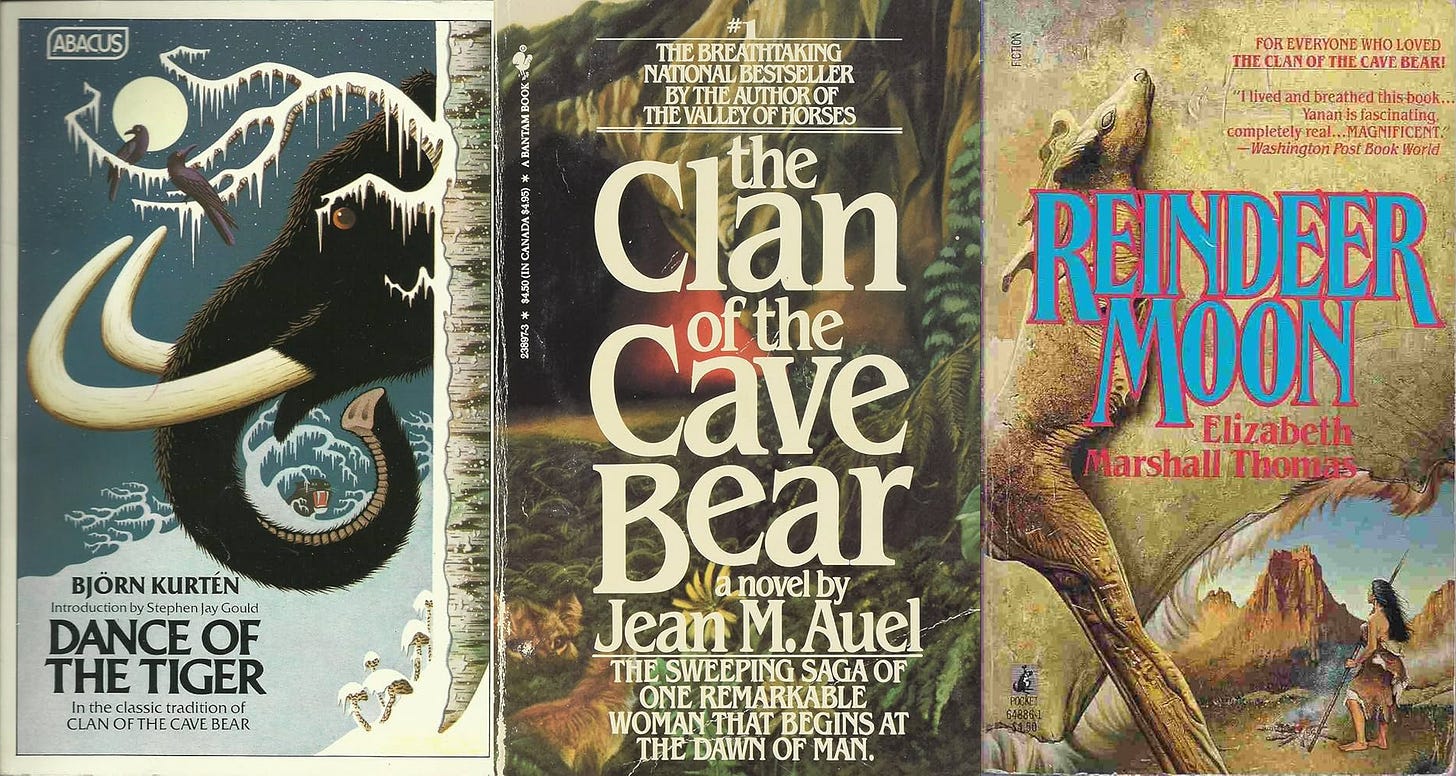

However, The First Flower People does mark a turning point, after which the Neanderthal question began to shift away from being exclusively academic. Several novels were published during the eighties and nineties, using Solecki as a reference, in which authors offered creative interpretations of the origins and behaviors of Neanderthals versus Homo sapiens – specifically on the nature of the interactions between the two.

Neanderthals came across as cognitively and culturally viable, albeit primitive, in works such as Elizabeth Marshal Thomas’s Reindeer Moon series (1987-90), Björn Kurtén’s Dance of the Tiger (1982), and most famously Jane Auel’s novel The Clan of the Cave Bear (1980), adapted as a popular feature film in 1987. In it, aspects of life we take for granted such as speech and the ability to cry are unique to Homo Sapiens. Although Neanderthals are depicted as having a culture, drawing upon research from Shanidar as well as the Aurignacian and Gravettian cultures, it is obviously less evolved.

So, while still perceived as the other, the veil nonetheless began to slip from the face of the Neanderthal post-Solecki, and certainly, these thought experiments that capture the mind can be more consequential than academic output like Solecki’s later critics. Remember, the most consequential depiction of Neanderthals perhaps in history was the brainchild of Marcellin Boule – a scientist who enlisted just even more creative liberty than the 20th century novelists to depict them as unintelligent brutes.

As Julie Drell writes in her 2000 essay Neanderthal: A History of Interpretation, “By the 1970s, a notion was firmly established that Neanderthals were just like us.” The question of Neanderthals being capable of ‘human’ intelligence had seemingly been overcome — with the undeniable assistance of Mme. Leroi-Gourhan and Ralph Solecki and their pioneering analysis of the Shanidar Neanderthals.

Solecki, R. (1971) The First Flower People. Alfred A. Knopf.

Ibid., 39.

Leroi-Gourhan (1975) “The Flowers Found with Shanidar IV, a Neanderthal Burial in Iraq” (PDF)

Top 10 discoveries of 2012 - Neanderthal medicine chest - archaeology magazine - January/February 2013 (2024) Archaeology Magazine. Available at: https://www.archaeology.org/issues/61-1301/features/266-top-10-2012-neanderthal-medicine

Hardy, A.C. (2017) New proof that neanderthals used plants to treat illnesses, UAB Barcelona. Available at: https://www.uab.cat/web/newsroom/news-detail/new-proof-that-neanderthals-used-plants-to-treat-illnesses--1345668003610.html?noticiaid=1345721008337

Shipley GP; Kindscher Evidence for the paleoethnobotany of the neanderthal: A review of the literature, Scientifica. Available at: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/27843675/

John Hawks (2022) A modern look at pollen from Shanidar and the question of ‘flower burials’, John Hawks. Available at: https://johnhawks.net/weblog/a-modern-look-at-pollen-from-shanidar/

Pomeroy, E. et al. (2020) New neanderthal remains associated with the ‘Flower burial’ at Shanidar Cave: Antiquity, Cambridge Core. Available at: https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/antiquity/article/new-neanderthal-remains-associated-with-the-flower-burial-at-shanidar-cave/E7E94F650FF5488680829048FA72E32A

Neanderthals had funerals with flowers, study suggests | CBC News (2020) CBCnews. Available at: https://www.cbc.ca/news/science/neanderthal-flowers-1.5469567 (Accessed: 24 November 2024).

Well researched. Well written. A veritable well of entertainment and information. Well, I'm a fan.

🏵️🙏🏵️